|

Notes

from

the Long Paddock Michael Kluckner ... working notes & pictures, as far as it got in 2009 before we decided to leave Australia & return to Canada © 2009. Posted in August, 2012 |

Return to "False Starts" page Return to home page

Send an email

|

This was

a proposal for an architecture book that almost got

published. University of New South Wales Press was

interested but needed a cash infusion from an institutional

or philanthropic sponsor (as is often the case with academic

books), about 10K they said. No commercial publishers were

willing, partly because I was an unknown to them, partly

because their audience is primarily urban, with urban

concerns and focus. It had been a long time, at least 20

years, since Australian heritage and architecture books were

common on bookstore shelves. The '70s and '80s, being the

lead-up to the bicentennial, were the heyday of that kind of

book there.

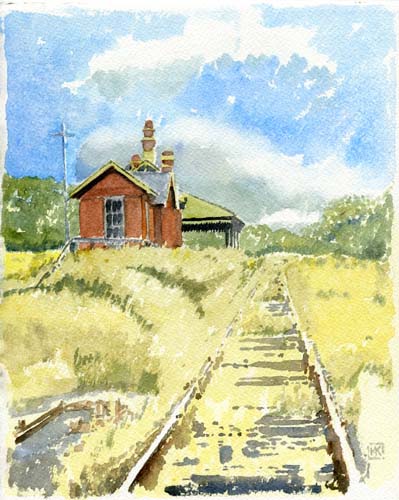

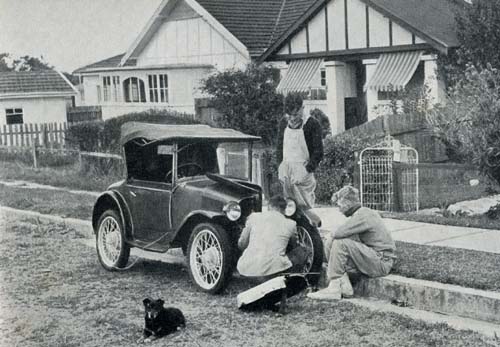

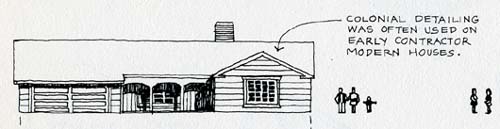

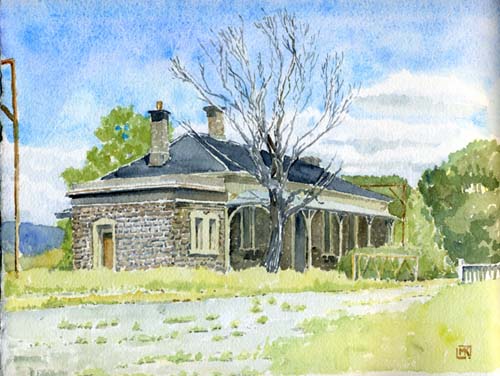

The "long paddock" is the roadside, the place where drovers, especially in drought-stricken periods, sought fodder for their sheep and cattle. So this was to be a book rather like Vanishing British Columbia or my Canada book, supplemented by a comparison of Australian rural buildings with their North American counterparts. Australia is really two countries: an urban coastal one and a rural one. Two solitudes, perhaps, but in spite of Australia's urbanization the sunburnt homestead with a few gum trees still seems to tug at the national heartstrings. A century ago, if you asked someone to describe their dream of a home, it would likely be the sort of classic tableau that I painted while travelling about in Oz: the spreading metal roof, the open porch, water tanks and a windmill, surrounded by enough land to make a living and offering clean air, sunshine, adequate water and independence. You can "read" Australian buildings the way a bushman reads the natural landscape, and learn a lot about climate, adaptation and the culture and history of the country. However, new generations of Australians will only have the written record to study and will live in a kind of virtual world, in terms of the physical evidence of their past, as the "roadside memory" on the long paddock crumbles into the landscape. I saw Australia through foreign eyes as I travelled and observed how settlers of an earlier era created their shelters, and pondered the differences in the landscape between here and those two New World countries – the USA and Canada – that share similar histories. On one level I was writing a road-trip book; on a more serious level, I wanted to highlight what I believe to be a national amnesia: the loss of the country's distinctive cultural landscape as the population urbanized and its architecture homogenized. The book idea got as far as a Powerpoint presentation, a lecture I gave once in Australia to a National Trust group and twice in BC (so far) after our return.  -Australia's old buildings, urban and rural, are an essential part of the country's uniqueness and should be revered by the public and promoted by the government as part of the country's "brand." -With the loss of this distinctive architecture and its replacement by current styles, Australia's built landscape is beginning to look like everywhere else in the world. -There are profound consequences, especially in terms of increased energy use, to the current types of suburban home design, town layout and shopping-centre construction. -There are lessons that old buildings and town layouts can teach modern Australians about environmentally friendly design, modest use of resources, and compact communities that are healthy and socially successful. -Government planning policies intended to streamline construction and development (especially in NSW) tend to reinforce a cookie-cutter mentality, further homogenizing Australia's streetscapes. Above: Railway gatekeeper's cottage at Goulburn Table of Contents: 1. Traditional town and city architecture 2. The evolution of the classic Australian homestead 3. Reflections on the differences in the rural landscape between Australia and North America/Europe 4. Foreign architectural styles in Australia: Georgian houses & terrace houses from Britain, the California Bungalow from the USA. 5. Distinctively Australian materials that were used around the country, such as sheet iron, fibro and render over brick. 6. The gold rush 7. A company town: Catherine Hill Bay 8. Pubs 9. Grand Estates 10. Shopping Villages 11. Holiday places in a more modest era: "mountain cottages" 12. Railways |

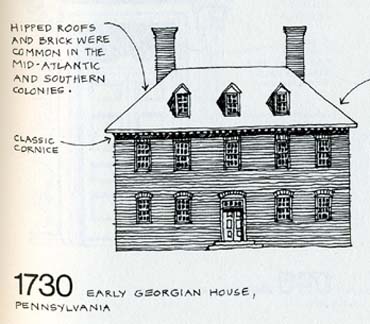

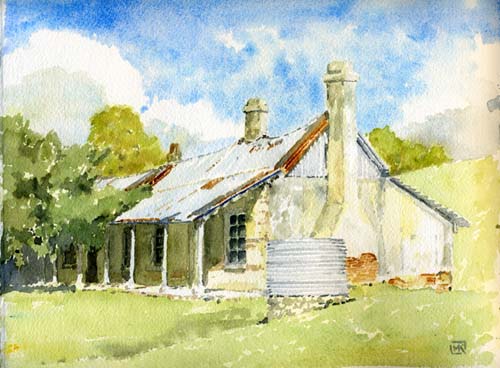

2. The evolution of the classic Australian homestead. The sprawling

Australian country house with its hipped roof and

bellcast eaves drew on the design of the bungalow, the

Bengali chauyari

(literally "four sides") and banggolo,

as remembered and adapted by British army

officers and settlers who had spent time in India. In

his monumental Australian architectural history,

published in the 1960s, John Maxwell

Freeland doesn't mention the word India once, but

the Historical Atlas of Australia published at the

bicentennial explicitly describes the style as the

"Anglo-Indian bungalow."

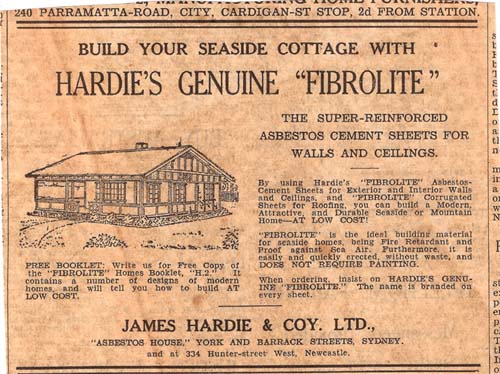

Above left: Experiment Farm Cottage, built in 1798 by Surgeon John Harris, who had spent ten years in India. Collitt's Inn, built in 1823 in Hartley Vale at the western edge of the Blue Mountains, is another early example of the style. Above right: a homestead of indeterminate age near the intersection of the Hill End-Sofala Road with the Bathurst Road. Its roof is in two sections, different from Experiment Farm's bellcast roofline, but the different pitch of the verandah's roof gives it a similar look. Rust on the roof: galvanized iron sheeting, as essential to Australian settlement as beer and meat pies. There wasn't another cheap material, like the softwood of North America, available to cover the surfaces of buildings in early Australia until fibro came along in the 1920s. The attached shed – galvanized iron over a crude frame – has the tired, slouching look of a bloke leaning against the wall of a country pub on a Friday evening. Below: two examples of a common variant of the hipped-roof style– a tiny gable vent at the ends of the roof ridge, which also became very common in 19th century suburban houses in places like Sydney and Melbourne. Both houses have a gabled front room, usually the parlour or lounge.  On the Hill End-Bathurst Road  Homestead on the Lue-Mudgee Road The key difference between the

classic Australian bungalow and other "new world"

dwellings such as those built in North America is the hipped

roof – more difficult to build than the gabled roof that was

the standard in Europe or North America. Why?

Perhaps as a response to hot overseas climates by

British people of a certain class when going to hot-climate

destinations – initially to India, then filtering down

through the Australian gentry to the shelters of the "bush

barbarians," as historian Manning Clark called them. British

settlers often built in this style in South and East Africa

and even, ironically, in remittance-men's enclaves in frigid

Western Canada. "This is what an expat's home looks like,"

they all but say.

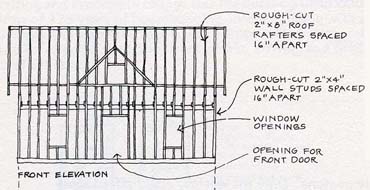

The other difference between Australian bungalows and most "New World" rural buildings of a century or more ago is the former's horizontality. Because there was no need to build steep-pitched, reinforced roofs to support winter snow loads, and because metal sheeting was a fairly light roofing material, rafters could span large distances and be set quite widely apart, using the minimum amount of expensive, hard-to-obtain timber. To keep the walls from being pushed outward by the weight of the roof, builders nailed ceiling joists to the tops of the walls and the bases of the rafters, creating a sort of truss as well as the support for a ceiling covering. Another reason for the horizontal spread of the buildings was the ease of creating a primitive foundation of posts or rocks. In the cold climates of Europe and North America, multi-storey houses took advantage of heat's desire to rise, but in warm country Australia it wasn't necessary to build upwards, include expensive staircases, and create complex post-and-beam framing. If a house were built of rubble or masonry, it could be built right on the ground, its floor perhaps dirt, boards on sleepers, or stone. There's a whiff of the "she'll be right" attitude in the casual, haphazard way many of these country buildings were erected.  And yet traditional Australian country houses are examples

of environmentally sympathetic design, well-adapted to

their surroundings, certainly when compared with their

modern replacements. Deep verandahs provided cool, shaded

spaces while, in some buildings, wide eaves or bracketed

window-shades kept the harsh sun and heat from the interior.

You rarely see bay windows, whose major role is to admit the

maximum amount of light into the interior, on traditional

Australian houses.

And yet traditional Australian country houses are examples

of environmentally sympathetic design, well-adapted to

their surroundings, certainly when compared with their

modern replacements. Deep verandahs provided cool, shaded

spaces while, in some buildings, wide eaves or bracketed

window-shades kept the harsh sun and heat from the interior.

You rarely see bay windows, whose major role is to admit the

maximum amount of light into the interior, on traditional

Australian houses. The volume of air trapped in the tall roof-space acted as an insulator during the long summer, compensating somewhat for the metal roof's tendency to radiate heat downward into the interior. The metal roof had another role, of course: catching rainwater for the ubiquitous galvanized tank set beside the house – another argument for a sprawling floor plan and maximum roof area. However, most houses were relatively modest in size, at least compared with modern homes, many of them with doors connecting between small rooms that could be closed off and heated. Multiple chimneys, such as the ones on the homestead above, indicate how individual rooms could be made comfortable during the short sharp winter. And, of course, people used the bounty of the agricultural countryside – the best wool in the world – for their winter clothing and kept warm that way, a contrast with the modern tendency to wear skimpy cotton or polyester year-round and to plug in a heater, powered by coal-generated electricity, whenever the weather turns cool. Like many contemporary Australians who reach for the air-conditioning when the weather turns hot, modern homes show little adaptation to the climate: the latter have narrow eaves, no covered porches, and large areas of glass. Air-conditioning is available, regardless of the environmental cost, in a country that produces more greenhouse gases per capita than any other in the world.  A vintage house in Carcoar, New South Wales. Brick walls, a deep verandah, a kitchen addition out the back and a tall hipped roof.

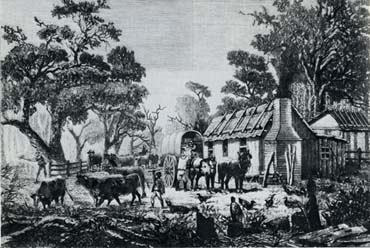

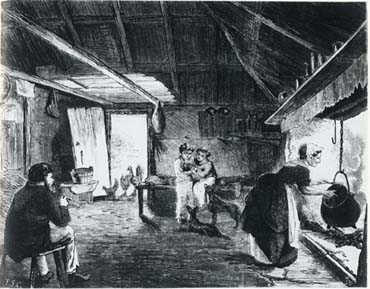

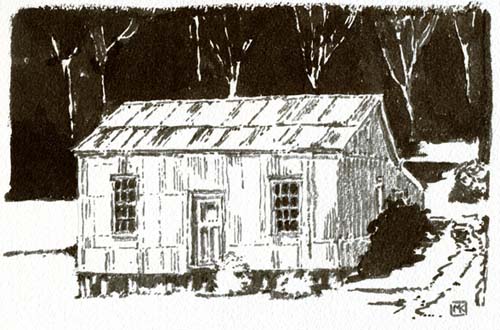

Above: Frederick McCubbin drawings of pioneer life in the late 19th century. On the left, A Victorian Selector's Homestead, (Australasian Sketcher, 25 September 1880); on the right, Interior of a Shepherd's Hut, Illustrated Australian News, 21 February 1870). The outside view shows a cabin little different from the ones built by Pilgrims arriving in North America in the early 1600s: built on posts, wattle and daub walls, a bark (shingled) roof, and a stick-built chimney plastered with clay mud. In the romanticised interior view from a decade earlier – romanticized at least to the extent that the family looks very contented and well dressed despite their rustic digs – the woman is cooking on a hearth, in the medieval manner, rather than on an iron stove. Hearths, with hobs (shelves to keep food warm) and hooks from which heating kettles and cooking pots hung, were both heat-source and cooking facility – the centre around which family life revolved – in early Australian homes. Freestanding ovens for baking bread were often built outside, well-away from the precious home due to fears of fire. In many homes there were "summer kitchens" in shed-roofed additions at the back to try to keep the heat of the cooking fire away from the living and sleeping areas – more of an issue once iron stoves became common than during the hearth era when most of the heat went straight up the chimney and the family spent the winter shivering picturesquely in the flickering firelight. Although metal stoves for heating had been invented in the 18th century – including the famous Franklin by American politician and polymath Benjamin Franklin in 1842 – the first practical wood-burning cooking stoves began to appear in the USA early in the 19th century. The most successful one, which could be loaded onto a covered wagon and sent out with the homesteaders on the Oregon Trail, was the Oberlin, patented by Philo Stewart in 1834. It is said that more than 90,000 of them were sold in 30 years, and doubtless many made it to Australia. In "Steam to Australia," (11 January 1856, New York Times), the correspondent noted "... in reading over the Sydney and Melbourne papers, ... we notice American cooking-stoves puffed up and glowingly described in the advertising columns." The most famous of the Australian-made stoves was probably the Early Kooka, whose colourful logo featured a kookaburra. Below: the room that was originally the kitchen of Canning Cottage, a semi-detached hipped-roof Georgian house in Launceston, Tasmania, as it was in 1999. Built in the 1820s for British officers who were garrisoned in the town, it was a very spare building, each unit having a front parlour, a kitchen-dining area (shown here) that has since been fitted with an iron stove in its hearth, and two small bedrooms up a narrow, steep staircase. At some point, probably a century ago, a shed-roofed kitchen addition was added to the back, followed roughly a half-century later by another shed-roofed bathroom addition bringing the plumbing indoors. It's the same rearward projection of the house seen in the Sydney terrace above.

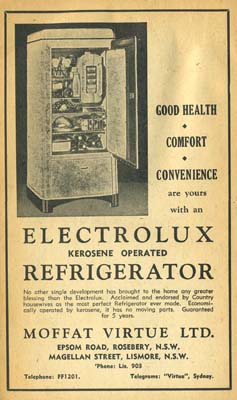

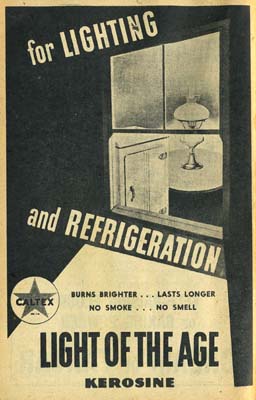

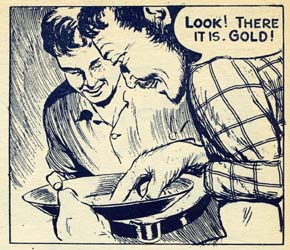

Above: Two 1930s

advertisements. In the Australian pantheon, the God of

Refrigeration has his own special niche. Unlike in Europe

and North America, there was no possibility of

ice-harvesting so food preservation was almost impossible.

Necessity being the mother of invention, a Scottish-born

journalist and tinkerer named James Harrison designed the

world’s first ice-making plant at Geelong, Victoria, in the

1850s. His first client was a brewery in Bendigo, then in

the midst of the gold rush. His efforts in the 1870s to

develop refrigerated ship chambers spurred the development

of the country’s hugely significant meat-export business.

Until small kerosene-powered refrigerators became affordable in the 1920s, rural people used ventilated meat safes hung in breezy verandahs and "bush coolers" – tin tubs covered in soaked hessian, where the evaporation of the water from the fabric drew heat from the food stored within. People joke about the wonders of technology arriving into country districts: "first kero lights, then kero fridges, then we got kero TV!" ***

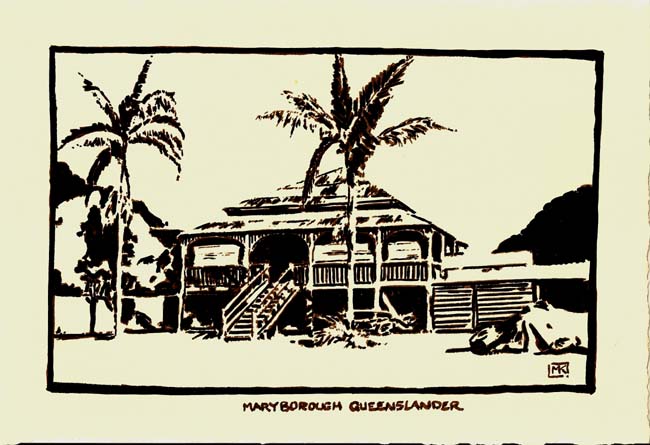

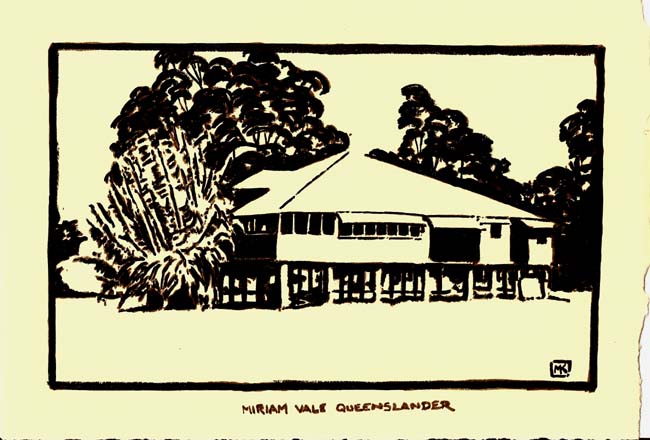

The most extreme and successful adaptations

to the Australian climate are the "Queenslanders," such as

the ones below in Maryborough and Miriam Vale in the

tropics: the house built up high on stumps (posts) to allow

a breeze underneath and space to store things and hang

laundry; wrap-around screened porches; pyramid roof; breezy

and open floor plan.

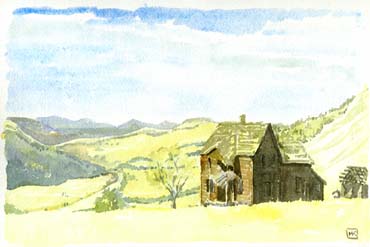

3. Reflections on the

differences in the rural landscape between Australia and

North America/Europe ...

Homestead in southern British Columbia, built about 1900 ... two-storey balloon-framed

buildings in North America compared with the sprawling

homesteads of rural Australia. The easy availability of

softwood such as pine, fir and spruce in North America made

the country buildings so different from Australian ones;

initially settlers built log cabins; later, once sawmills

became common, everyone built with a balloon frame and

machine-made nails. They covered walls with drop siding,

called weatherboard in Australia, and shingles, and used

shakes or shingles for roofs. This was the same for most

town and city houses except in areas with a lot of good

brick clay, such as the swath of North America including

Pennsylvania and Ontario.

The balloon-framing technique, together with machine-made nails, came to Australia with the miners from California in the early 1850s.

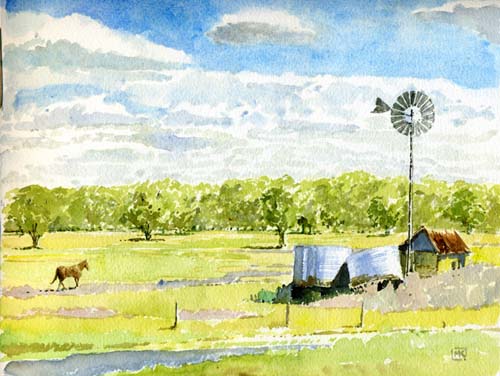

+ sheds, not barns  Wallaby Rocks along the Turon River in NSW.

Wallaby Rocks along the Turon River in NSW. As there is little need to store fodder, the Aussie agricultural shed is a much more modest affair than the grand barns that typify the rural landscape in the cold parts of North America. Galvanized iron sheeting is the most common material, nailed onto a simple timber frame. Compare an Australian shed to the sort of dairy barns typical of the Fraser Valley near Vancouver. ...and water  Windmills are common on the North American plains but the above-ground water tank, as practical as it might be in Australia, is not of much use in colder climates because of winter freeze-ups; similarly, the use of eavestroughs for harvesting water from roofs doesn't have a lot of use in climates where winter snow and ice wipe them out. Building for snowload: Sandon in the Kootenays in British Columbia

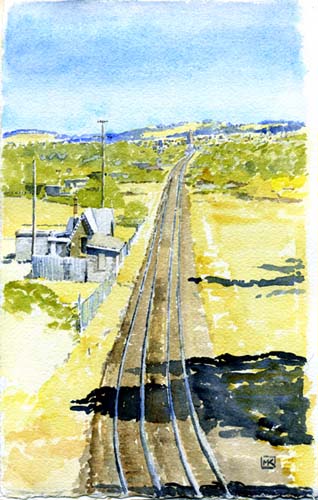

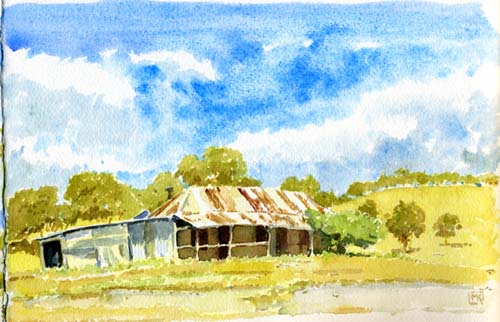

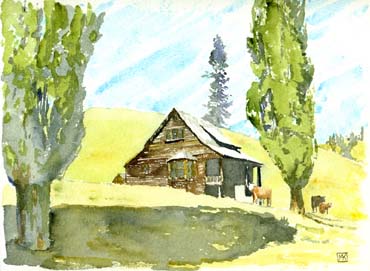

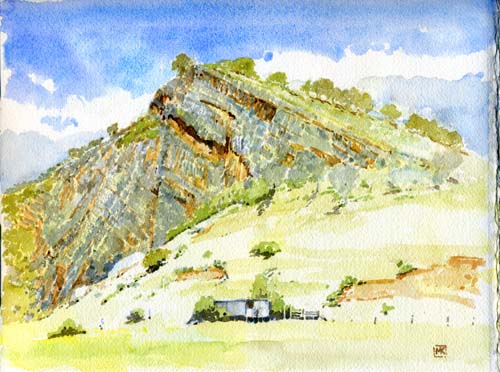

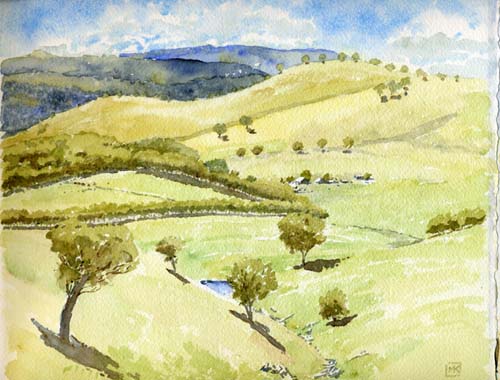

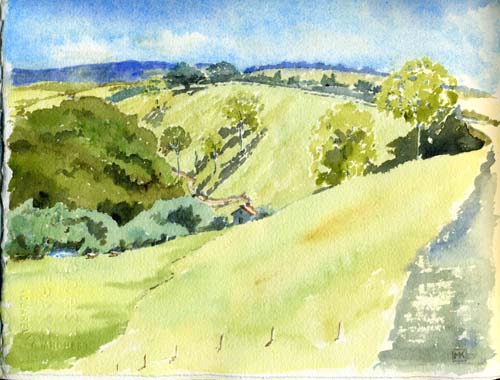

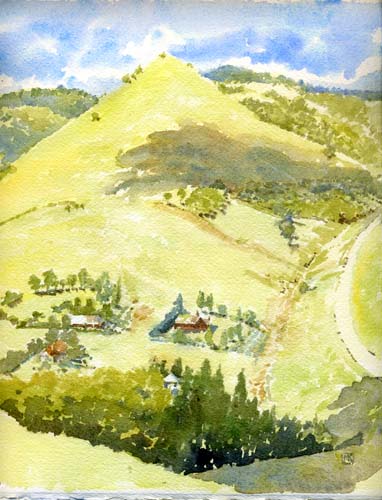

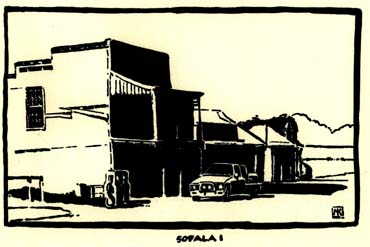

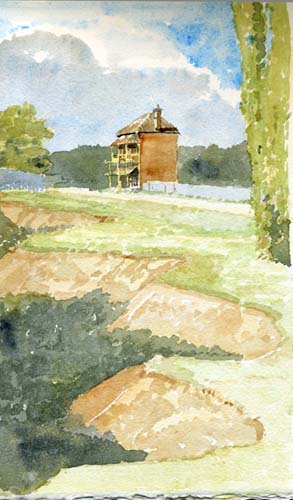

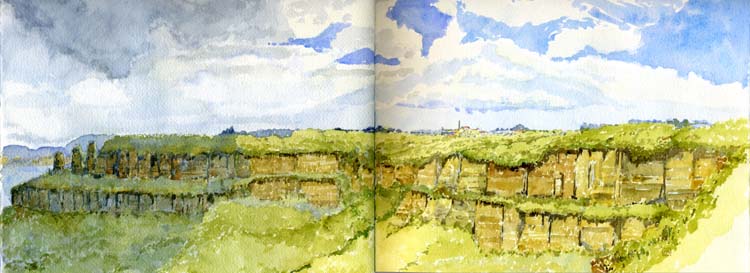

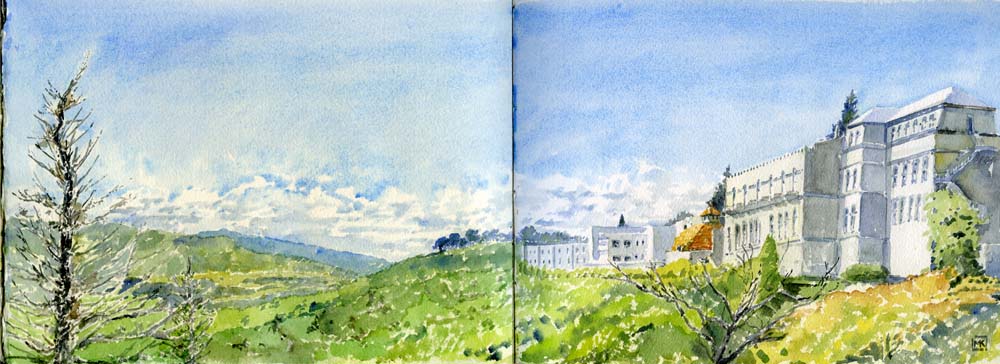

Watercolours from a summer roadtrip through the hills northwest of Bathurst in New South Wales, 2008 It is rare to find seeping

groundwater or permanent rivers forming even small lakes

in Australia, so the farmer has to corral run-off from

torrential downpours, pushing a berm of earth across the

water's path to create a dam, in order to water livestock

and crops. This is often supplemented by bore water pumped

to surface tanks, most picturesquely by the windmills that

still dot the countryside. The little dams reflecting the

blue sky have a similar look to the "potholes" of prairie

farmers in North America. I found my eye (and paintbrush)

drawn to every patch of water on the landscape, for water

equals survival.

Near Tarana, western edge of the Blue Mountains, 2008 By way of comparison, a spot somewhere/anywhere on the Canadian prairies, with old farm buildings reflected in a small lake. |

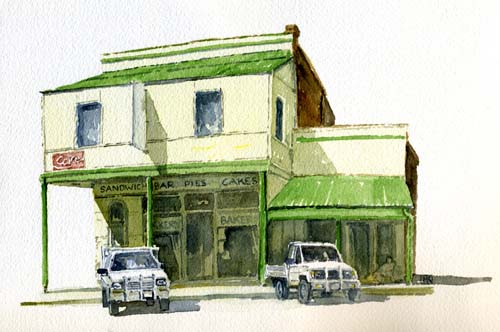

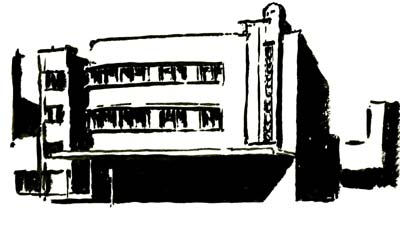

10.

The shopping villages in suburbs and towns, compared with

the American-style strip malls and shopping centres of the

modern nation. Westfield, the Australian-owned shopping-centre

developer, is one of the largest in the world.  "Sketch of Lawson to remember it by", 2007, (see the bottom of this page for a larger version). Lawson is a town midway along the Great Western Highway in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. I painted a 10-foot long 10-panel oil of its shops as they were in 2007, when we moved there, knowing it was going to almost totally wiped out by highway expansion.  Above: a milk bar in Molong. Once upon a time a landmark of every NSW and Victorian shopping street and country town, milk bars fit into the same cultural niche as the old soda fountains of the USA a generation or two ago. A rougher version of a tea room to be sure: coffee, milkshakes, cokes, burgers, chips, jaffles, salad sandwiches on white bread, a fan turning lazily on the ceiling, colourful plastic strips in the opened doorway to try to keep the flies outside, a refrigerator for milk and pop, a freezer for Streets ice creams and paddle-pops, Cherry Ripe and Violet Crumble chocolate bars and lollies such as Jaffas for sale on the counter, a few tables or booths, sometimes a jukebox… Gradually wiped out by the more car-oriented culture of the last generation and the invasion of foreign burger chains and "handi-marts" attached to petrol stations.  The elements of a country town: wide main street, parking at a 45 degree angle, mix of commercial buildings and small homes, pub with open verandahs and TV antennae/satellites, road heading straight off into the distance over the rolling hills.  The Wattle Flat general store and Caltex station |

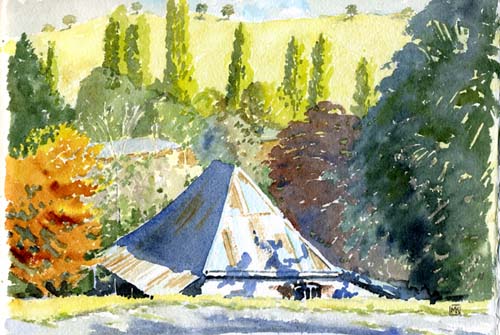

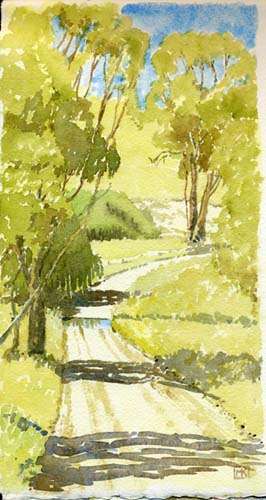

And, as a reflective

end-piece, exotic trees as evidence of settlement in the empty

landscape

South of Bathurst, NSW, on a sunny autumn day in May, where poplar trees have seeded themselves along a creek. Long after the countryside is abandoned and everybody lives in cities along the coast and all the buildings have blown away, there will be non-native trees dotted about – are they feral trees? Will a future environmental department set out to eradicate them? This is a similar situation to that in British Columbia, where poplars, willows and acacias mark settlement sites in the Fraser Canyon and the Boundary country. |

Return to "False Starts" page Return to home page

Send an email

Above:

the working-class terrace in a Victorian-era British

city in the subtropics. Middle-class terraces in areas

such as Paddington and Glebe in Sydney are larger and

airier, sometimes have more rooms, but essentially stay

with the same layout.

Above:

the working-class terrace in a Victorian-era British

city in the subtropics. Middle-class terraces in areas

such as Paddington and Glebe in Sydney are larger and

airier, sometimes have more rooms, but essentially stay

with the same layout.

The

fine

stone station at Bowenfels, NSW, on the edge of the city of

Lithgow, is boarded up and abandoned, ironically within

sight of the local McDonald's – the great emblem of the car

culture.

The

fine

stone station at Bowenfels, NSW, on the edge of the city of

Lithgow, is boarded up and abandoned, ironically within

sight of the local McDonald's – the great emblem of the car

culture.