Contact me Go to home page Return to main travel page

| Rajasthan (en route from

Delhi & Agra) 2009 Michael Kluckner We

took the opportunity presented by being in the "neighbourhood" (the Emirates trip) to fly the 3

hours to Delhi

from Dubai and travel in one small part of teeming immense

India. Rajasthan is the classically beautiful desert State on

India's west coast adjoining Pakistan; Agra, in Uttar Pradesh near

Rajasthan's eastern border, is home to the immortal Taj Mahal; and

nearby Delhi, with its 13 million inhabitants,

is a place to view the contrasts between the Old Delhi of the Hindu and

Mughal eras and

the New Delhi of the British Raj in its twilight years. A theme common

to the areas we visited was the grand Mughal

civilization of the 16th to 18th centuries, of Akbar the Great and

Shah Jahan, of the Red Fort in Delhi and the "pink city" of Jaipur.

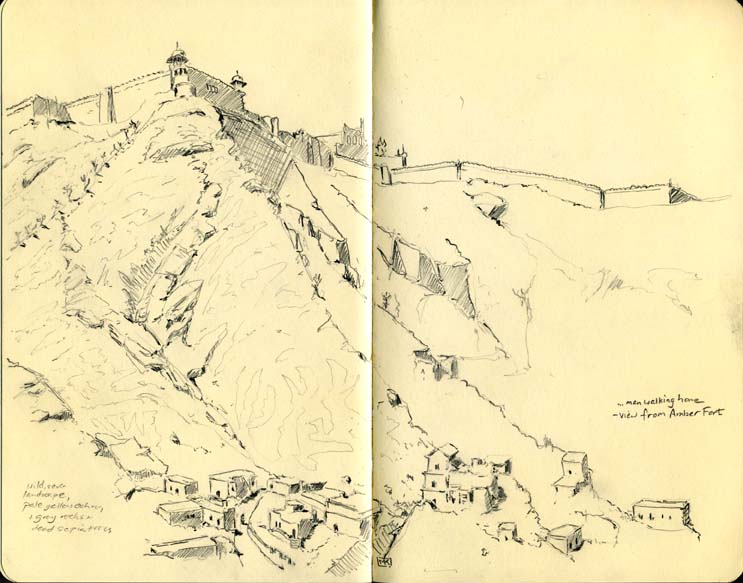

Attempting

to draw the spectacular view from Amber

Fort while also

attempting to answer a million questions. "You're from Australia? Ah,

Aussie! Aussie! Aussie! Oi! Oi! Oi! Ricky Ponting! [sporting chants and

the name of the current cricket team captain] Sydney! Melbourne! I

have many

friends there.... what are you doing???"

In any of the places where I attempted to draw or paint, I had at most

5 minutes before I was surrounded by young men who stood right there, often

mere

inches away, sometimes blocking my line of view. Oh for a fortful of

reserved, reticent Canadians at a time like that.... Attempting

to draw the spectacular view from Amber

Fort while also

attempting to answer a million questions. "You're from Australia? Ah,

Aussie! Aussie! Aussie! Oi! Oi! Oi! Ricky Ponting! [sporting chants and

the name of the current cricket team captain] Sydney! Melbourne! I

have many

friends there.... what are you doing???"

In any of the places where I attempted to draw or paint, I had at most

5 minutes before I was surrounded by young men who stood right there, often

mere

inches away, sometimes blocking my line of view. Oh for a fortful of

reserved, reticent Canadians at a time like that....India was the most difficult place where I've ever tried to paint. It is immensely crowded, people are aggressively curious (friendly), and there is absolutely none of that sense of aloofness, of personal space, that allows a travelling artist in many parts of the world to contemplate the surroundings uninterrupted. I ended up spending my time drawing frantically in the small Moleskine sketchbook I carry and had only a few opportunities, such as the hotel rooftop in Agra with the view of the Taj Mahal at dawn, to get out the watercolours. Thus, much of what appears below was painted or completed when I got back. I needed good sable brushes to add texture and layers of colour to capture the particularly grainy, dusty quality of the place (I usually carry just a squirrel-mop travel brush that's okay for washes), and the landscape and clothing colours forced me to use other paints than what I normally carry: semi-opaque gouache colours such as Jaune Brilliant and a hot pink called Thio-Violet, to supplement my paintbox's Rose Madder and Indian Red. And the light itself is somehow thick, fat; the high sunlight is diffused through dust hanging in the air. Logically one would have to crank up the colour temperature, but there was something else that had to be added -- a kind of energy, of agitated movement, that crackled through almost every place. The best of our photographs from India, and narrative about other aspects of our trip, are on Christine's blog. |

|

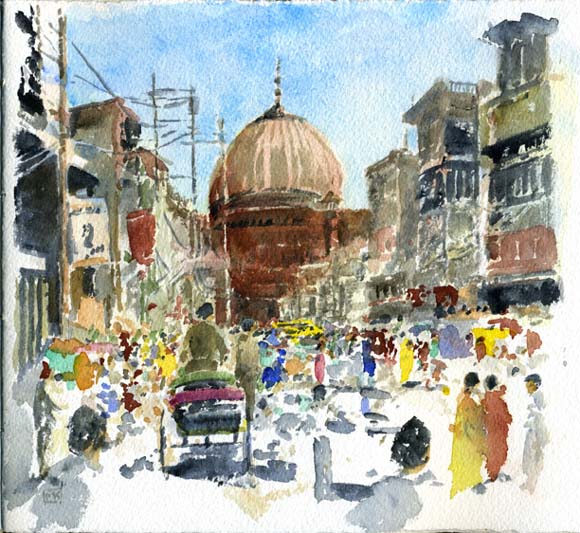

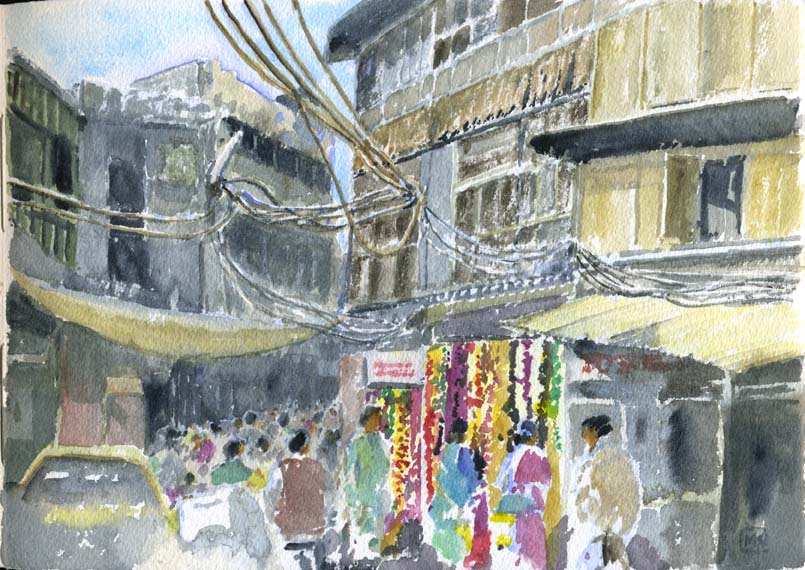

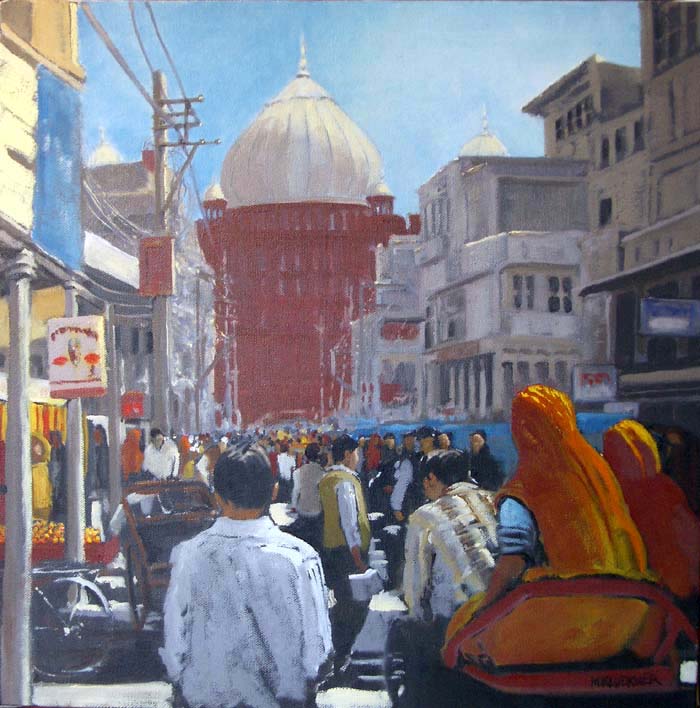

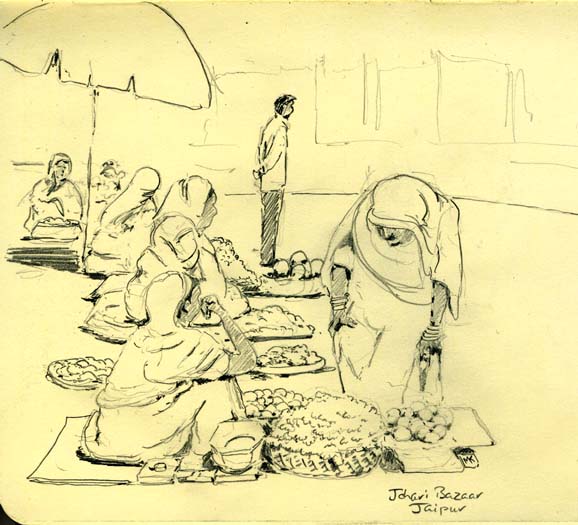

Three

images of Chandni Chowk, the Old Delhi bazaar of narrow winding lanes,

crumbling concrete and brick buildings, tangled electrical wires and people.

People on foot, in rickshaws, scooters and tuktuks (the

3-wheeler taxis with motorcycle handlebars and gearing). People

trading from shops and touting in the streets, shouting into mobile

phones, cooking chapattis and making chai tea to sell on the edges of

the narrow lanes. Cows munching through

garbage, stray dogs asleep in gutters inches from passing cart wheels.

The

infinite numbers of white shirts on the men and colourful saris on the

women. Fabric hanging in shopfronts. Noisy and confronting streets,

like a

video game where you're caught in a wave rolling you along while

dodging

oncoming human and mechanical missiles. But safe -- India never felt

threatening or hostile at all. The watercolour to the left I did while we were there, the others after we returned. We realized that our photos somehow froze the motion, somehow made it seem as if there was a lot of space between people and vehicles, which there wasn't. No patch of ground remained unoccupied for more than instant. Thus the broken brushstrokes and the agitated patches of raw colour. |

A later addition, in oils at home:

In

the hot, bright sky above Delhi's Red Fort the kites circled, slow and

languid, a reminder of the transitory commerce and humanity

of the chawls below. Eternal India, like the rivers and the buzzards in

the desert. On the final day we found ourselves at Connaught

Circle, its arcaded buildings based on the English city of Bath. Once

the commercial centre of New Delhi, it is now crumbling and ramshackle,

and we decided to catch the gleaming new Metro back to the more

pleasing, organic

decay of Chandni Chowk. Not surprisingly there were beggars lining the

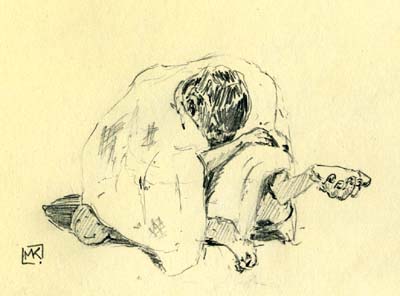

exit from the station. Beggar from memory -- no, I didn't stand there and draw him or take his photo like a trophy. |

|

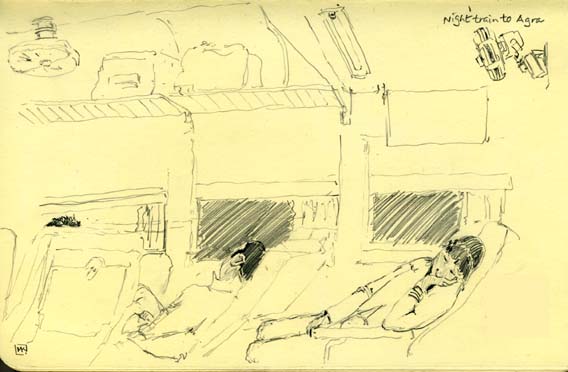

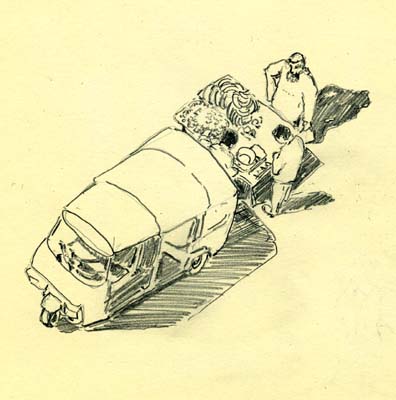

| On the night train to Agra. We were travelling in a sort of first class carriage called 2AC, and had what appeared to be the advantage of glass on the windows (as opposed to bars across the "windows" and wooden benches in second class), but it didn't matter that it was twilight when we started because the glass was almost opaque from age, wear and abrasion. Christine describes on her blog the run & jump we did to catch the train; once on, we settled into its slow, rocking progress, and as the other passengers quieted down I whiled away the time drawing. Most buses, whose chafed old windows could at least be opened, offered a better view of the countryside. |

|

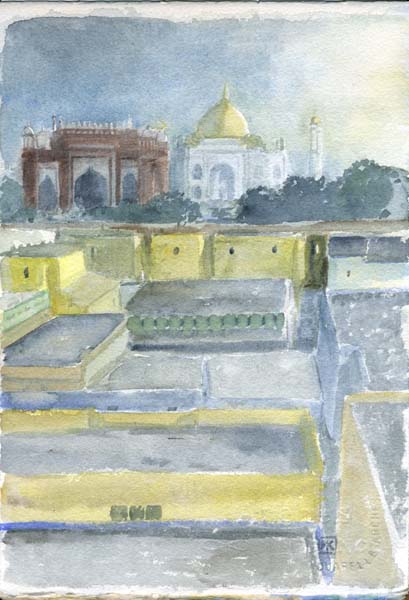

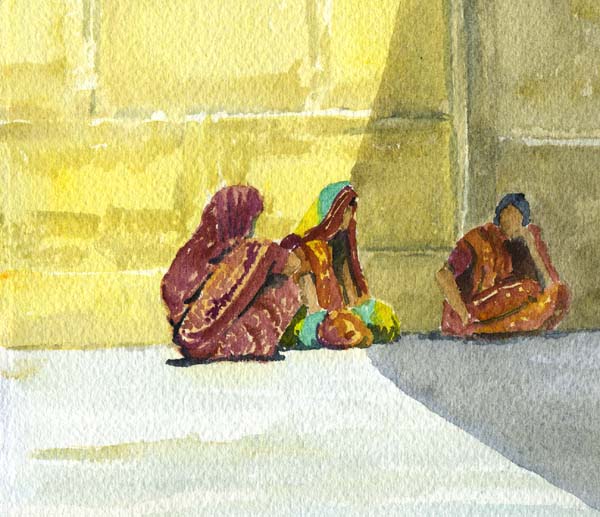

Six-fifteen

a.m., up on the roof of our tiny hotel in Agra, as the rising dawn

caught the dome and minarets of the Taj Mahal. As with the

Acropolis, the Coliseum, the Alhambra and the Hagia Sofia, I

want to remember having put it into a sketchbook when I'm old and

drooling in the nursing home and they've taken away my DVD player. As

Christine wrote, we knew our photos would look like everybody else's. I thought I would be able to take my art stuff in with me when we fronted up to the entry gate about 6:45, and had visions of quietly sitting and painting the famous Taj and its symmetrical gardens. But it was not to be. The security is so tight, anti-terror and anti-vandal, that my watercolours and my pencil didn't survive the search. I could see if I was standing there with a fistful of magic markers or a can of black spray paint, but watercolours? "Same rule for everyone, sir" said the 200-pound Army sergeant with the machine gun. So we wandered around the beautiful park, so serene compared with Agra's streets, with the little camera framing scenes to paint later. Below on the left is one of the minarets at the corners of the Taj's terrace; the marble is so smooth, so polished by the thousands of stockinged and bare feet, that it reflects shapes like pavement after a downpour. Below on the right, a solitary worker with a standard Indian broom swept the floor beneath one of the Taj's grand arches. |

|

|

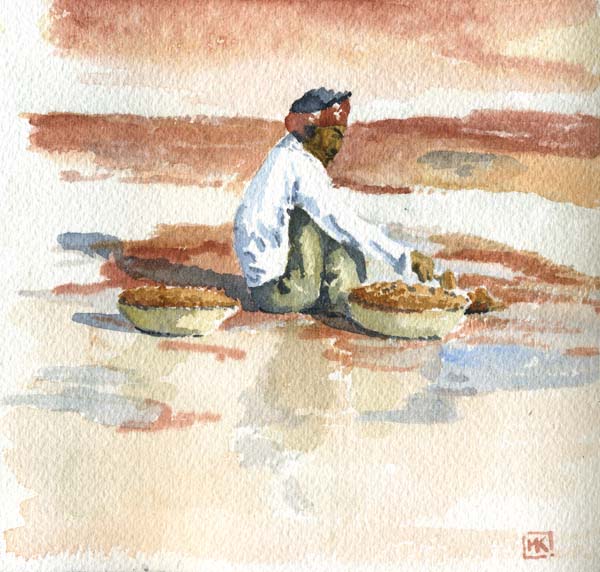

| Along the Yamuna River that flows through Agra past the Taj Mahal, a pavilion/temple, or perhaps it was once a guardhouse, emerged from the morning mist. The Yamuna is a tributary of the Ganges, both of them sacred rivers, their eternal flow the mystic lifeblood of the Hindu faith. What a contrast, what a place of unchanging tranquillity on the edge of bustling, poverty-stricken, crime-ridden Agra. |

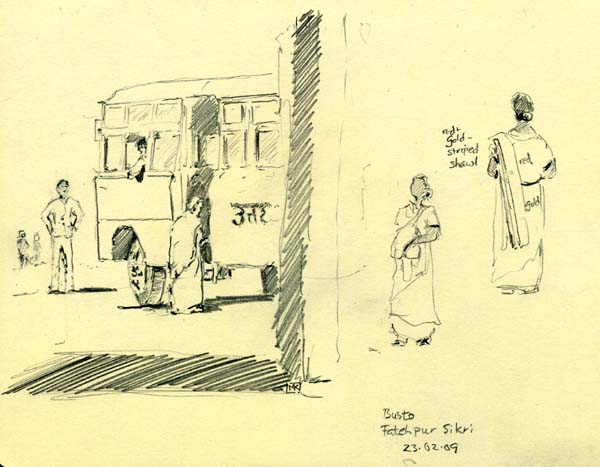

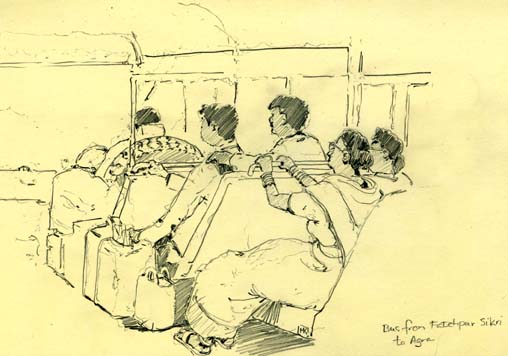

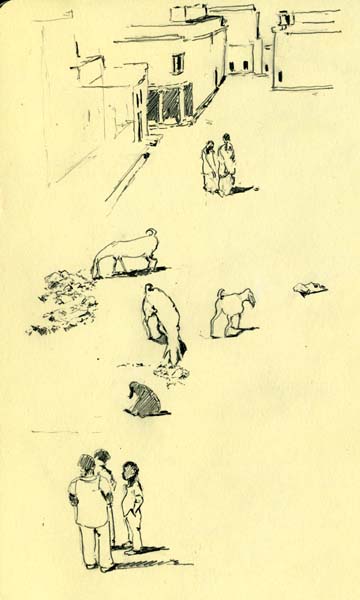

| I drew the people on the local bus as it bounced along the rutted, holey roads -- you can see the shaky underdrawing from the jolts and vibration -- and swerved around carts, motorbikes, rickshaws, donkeys, flocks of sheep and goats, purposeful water buffaloes and ambling cows while challenging oncoming traffic with its blaring horn and flashing lights. Many passengers slept, others hung on and focused grimly on the road ahead, perhaps reaffirming their belief in reincarnation. The narrow aisle was full of luggage and boxes, and a large spare tire, still showing a little tread, slotted into the space behind the driver's seat. Our small bags fitted onto the overhead racks -- a relief as the alternative would have been to throw them up on the roof of the bus where they would have been fair game for the thrill-seekers riding up there. |

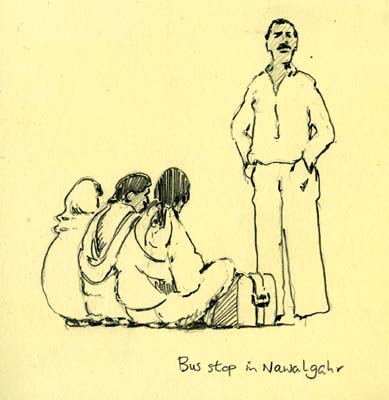

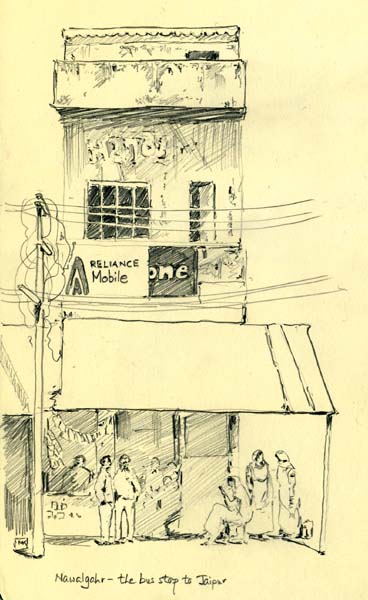

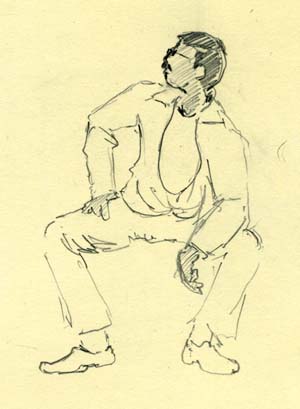

Killing time at the bus stop. We were going to catch a 5:40 am bus from Nawalgarh to Delhi and arrived there at 5:20 am, no shred of light in the eastern sky, in time to see the bus pulling away -- the schedule had changed! The next bus was scheduled to leave at 9:20 so we got there at 8:30 and finally left at 9:45. Everything works in India, eventually, but it would be difficult to be, say, a German there. |

|

|

|

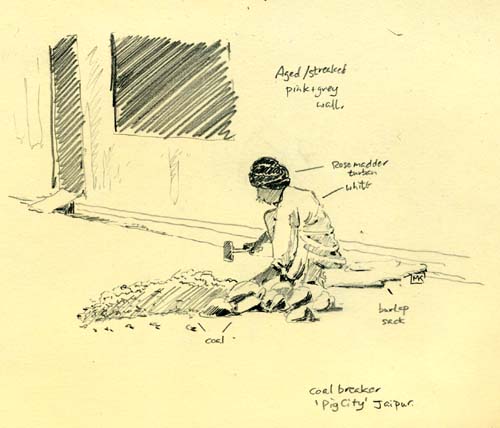

| (Left)

This

man's métier was presumably buying large lumps of

coal and reducing them with a hammer into smaller lumps, a job he did

squatting on the edge of the street,

then selling them at a profit

to the local women for their cooking fires. "Pig City", according to

our auto-rickshaw driver, was an area of Jaipur occupied by a

very low Hindu caste who ate pork. Or, perhaps, they kept pigs just to

clean

the place up? There is always garbage on Indian streets, but

most of it doesn't last long as cows and goats make short work of it.

Perhaps part of the saving grace of Indian life, in the sense of public

health and disease prevention, is that most people are vegetarians. (Right) Goats not drawn to scale! -- doodles from the rooftop of our haveli in Nawalgahr (see below). The goats are really the comedians of Indian towns -- choffing paper bags and leaves, posing picturesquely atop piles of concrete rubble, romping up and down the streets. They always look well-fed and mischievous. I presume they're kept by the Muslims who barbecue them, their meat usually referred to as mutton on English menus, and use their milk for drinking and cheese-making. Hindus appear to prefer cow's milk for drinking and for the cheese that goes into palak paneer, for example. |

|

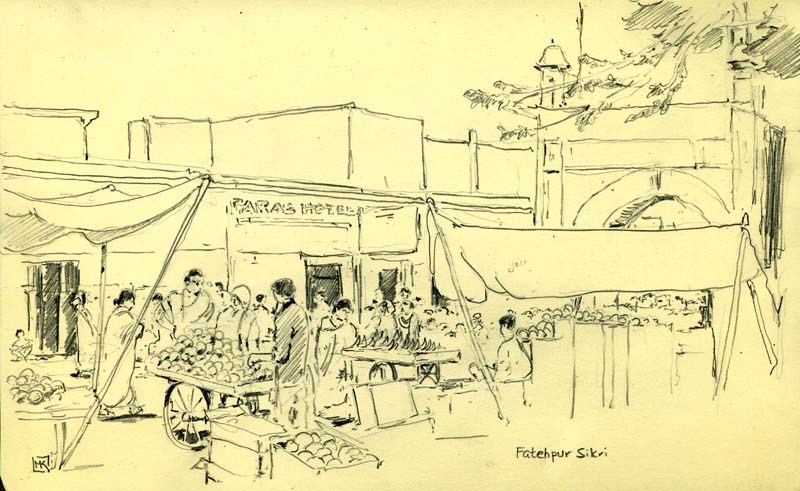

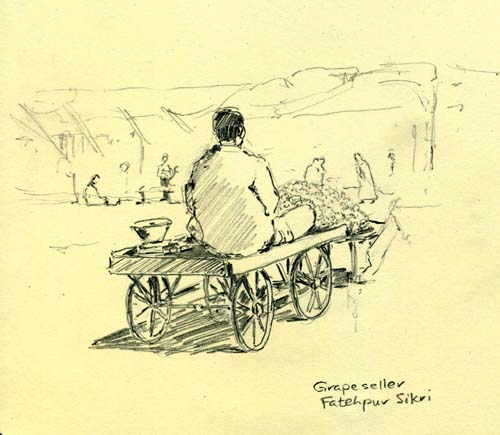

Market town: fruit and vegetables in glorious abundance for sale on the main road in Fatehpur Sikri. It appeared that the farmers arrived into town very early in the morning, then turned their camels and donkeys over to the care of children who took them to the outskirts for pasture and water for the day. The more prosperous farmers arrived in their tractors, usually with a half dozen or more people clinging to every surface. |

|

|

| Amber (pronounced Am-air), is a dozen or so kilometres from Jaipur. The magnificent fort and battlements occupy high, craggy ground, its protective walls running up and over the nearby hills like China's Great Wall. This is the sketch I was working on when Christine took the photo of me with my companions at the top of the web page. |

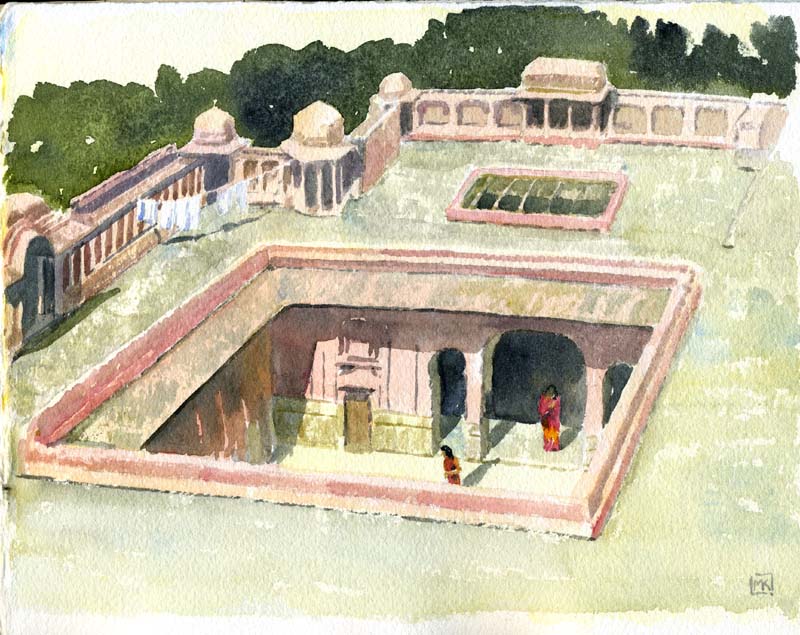

| (Above) The roof of a haveli -- a traditional dwelling -- in Jaipur. So much of Indian life reflects the extreme contrast between outside and inside, between the "enclosed space" (haveli's meaning in Persian) of the home and the free-for-all of the streets. Once you're outside, there's little opportunity to find a quiet cafe as one would in Europe or North America, or a park with a secluded bench; instead, you have to retreat to the calm of a hotel room or, if you're an Indian, the sanctum of your home. And for women, many of whom still live in purdah (seclusion), their home offers them an opportunity to go about unveiled and -- usually -- unobserved. |

|

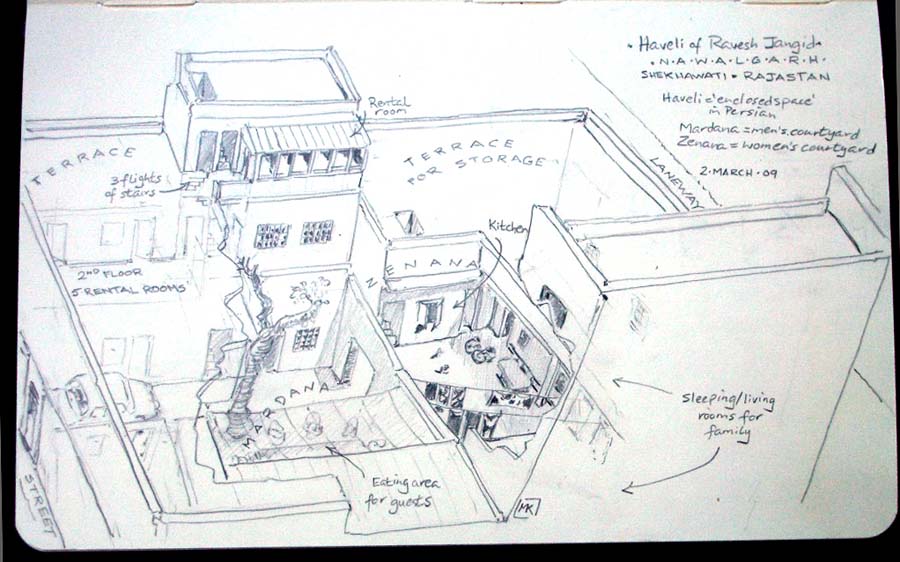

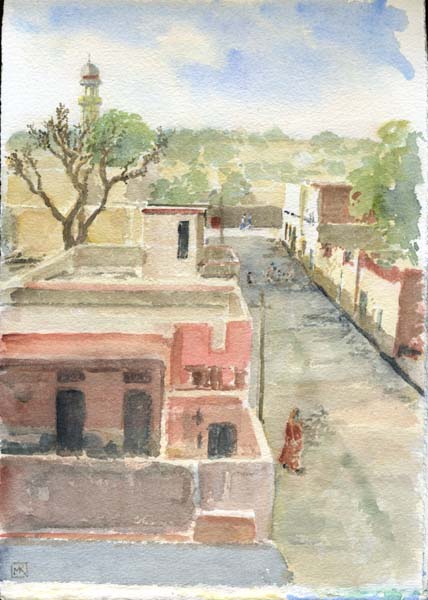

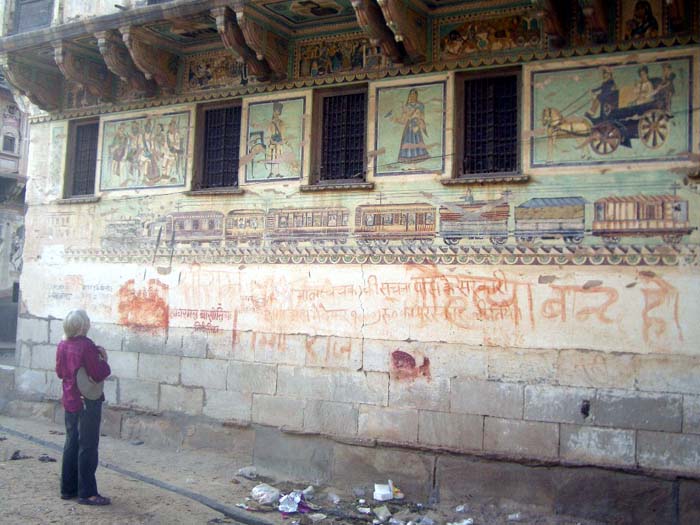

In

Nawalgarh in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan we stayed in the

tourist pensione of a Brahmin family who are engaged in the

efforts to create sustainable agriculture and tourism in their

drought-stricken region. Their organization, Les Amis

de Shekhawati, is also very involved in the attempts to

restore the murals on the old merchants' houses (see below). They had

adapted a traditional haveli, built

two generations ago, to provide a combination of family privacy and

social space for guests. In the traditional haveli, business associates

and friends of the owner would be entertained in the mardana, while the

women could live in purdah with their children in the zenana. The women

can literally let their hair down, and you quickly appreciate the

tranquility

of their traditional homes, the cleanliness and calm compared with the

dust and noise of the streets. At night the street door was locked

and we felt safe within the walled compound; once or twice in the flat

dark night we were

awakened by dog fights in the streets, the weird howling like something

from a

vintage Pink Floyd album, and felt like it must have been in medieval

times. Inside safe, outside monsters.... (Below) from the roof terrace of the haveli. The minaret in the distance bristled with loudspeakers, the recorded muezzin awakening the town regardless of creed or colour at 5 a.m., then four times more before shutting down for the night just after 8 p.m. |

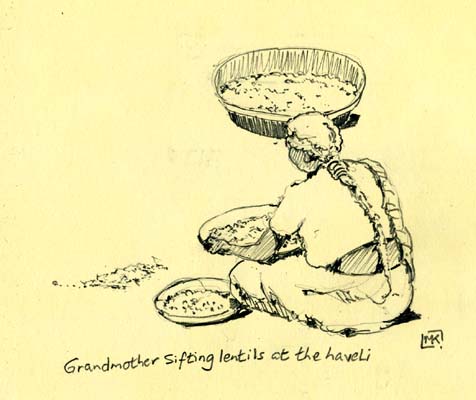

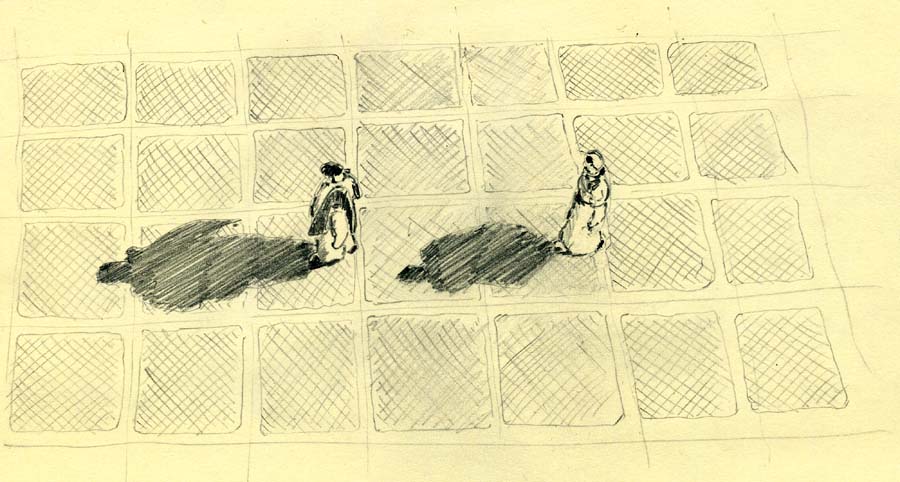

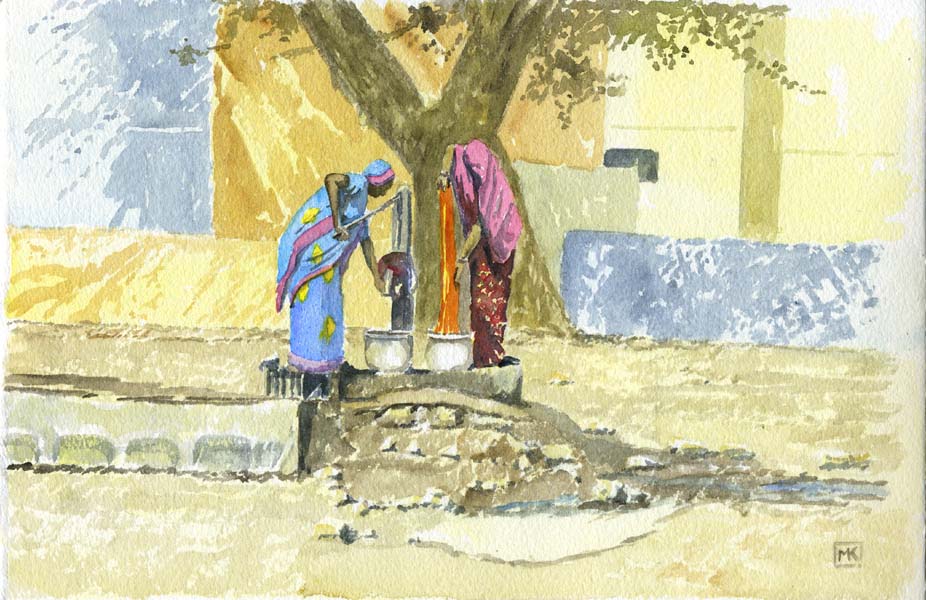

A man rendering the tiled surface of a terrace with terracotta

Women washing clothes at the town pump in Amber

|

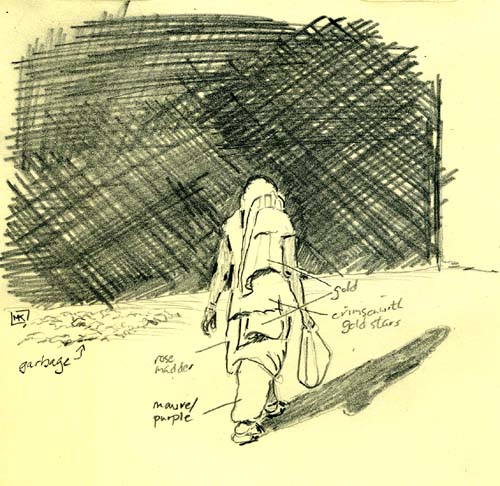

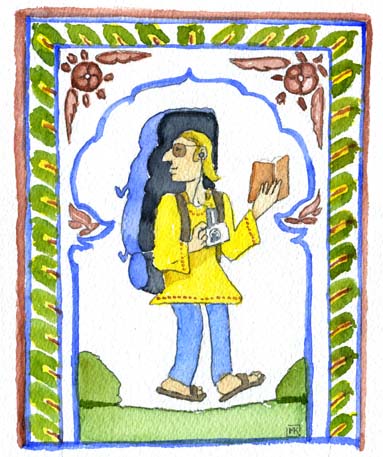

A

backpacker, in the style of Rajput painting and the Shekhawati murals.

We were amused to see the many westerners travelling through India as

our youthful contemporaries did 40 years ago. With ethnic clothing and

shoulderbags, many of

the women sporting henna tattoos on their hands and bindis (the drop of

red colour between the eyebrows), carrying digital cameras, iPods

and

copies of the Lonely Planet guide, they pursue their goals of

adventure, knowledge and, in many cases, their own spiritual awakening. And it's so cheap to travel compared with, say, Europe. India, like its Southeast Asian neighbours but unlike China or Japan, had no tradition of landscape painting. The Hindu and Buddhist cultures produced figurative art, mainly sculpture plus some painted murals; the Mughals who invaded in the 1500s brought with them a "Persian miniature" type of painting that evolved into the Rajput style and contained only the most stylized indications of landscape. Nawalgarh was an important stop on the caravan routes from the Gujarat ports to central India, and its prosperous merchants in the 19th and early 20th centuries decorated their elaborate havelis with murals. As you can see from the photo below, the murals of a century ago contained all sorts of contemporary motifs, including the colonial English in their carts and cars and trains. If the mural painting tradition is to continue, it ought to depict backpackers. |

| "How long have you been in India for ....? Oh, it is not enough." |

Contact me Go to home page Return to main travel page

Artwork & text © Michael Kluckner, 2009