Open the main article in this window

Thoughts on Japanese (& Chinese) Painting

Michael Kluckner

I learned in a Fine Arts course at UBC about 50 years ago how

Japanese art evolved from Chinese painting, especially the quick

and spontaneous Zen styles that appeal to me as a traveller and a

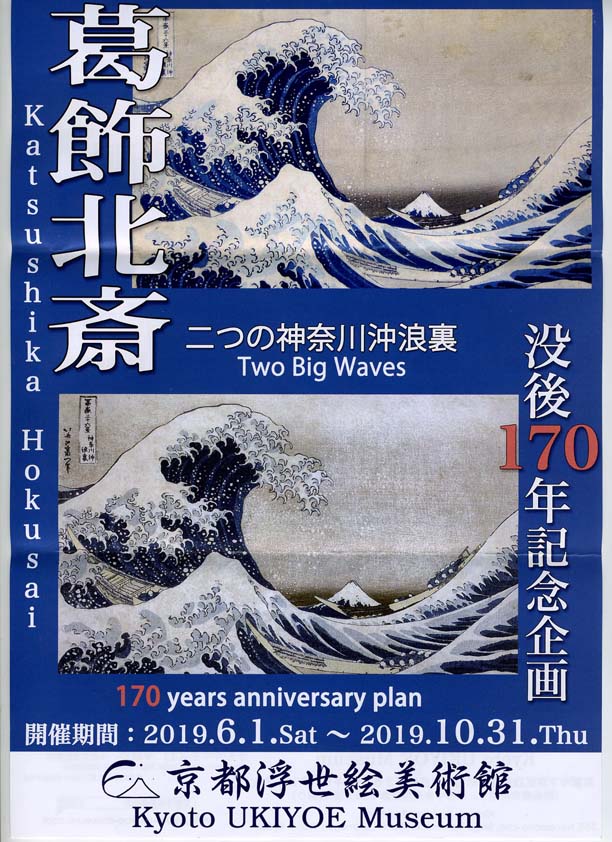

sketcher. The master was Katsushika Hokusai, whose "manga" has

been republished in a large volume called, not surprisingly, Hokusai

Manga, a cornucopia of his 18th and 19th century drawings of

people, animals and landscape vignettes (manga means 'whimsical

drawings'). Hokusai is also the master of colour wood-block

printing called ukiyo-e, most famously in his 36 Views of

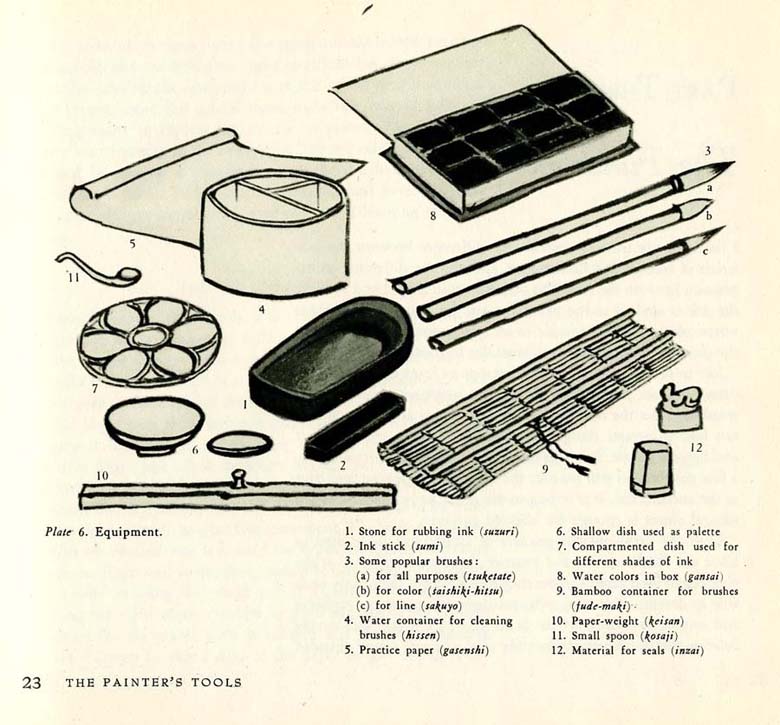

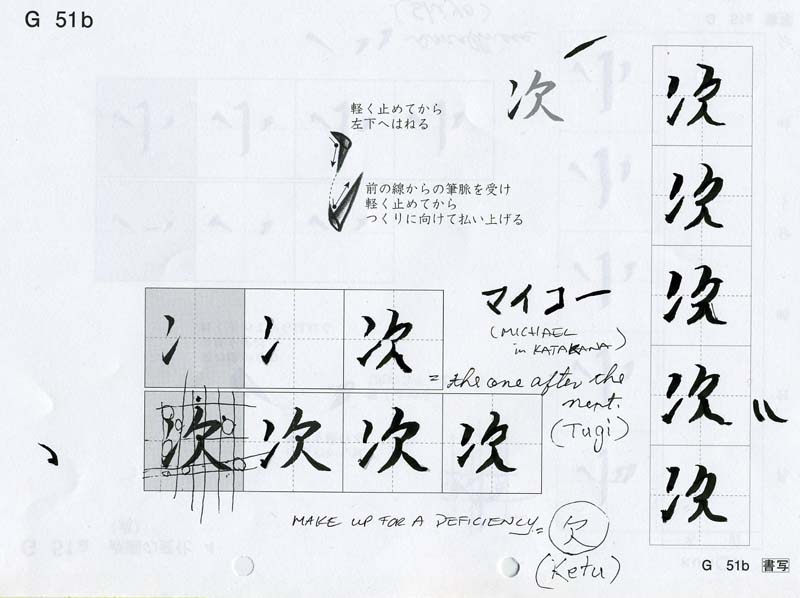

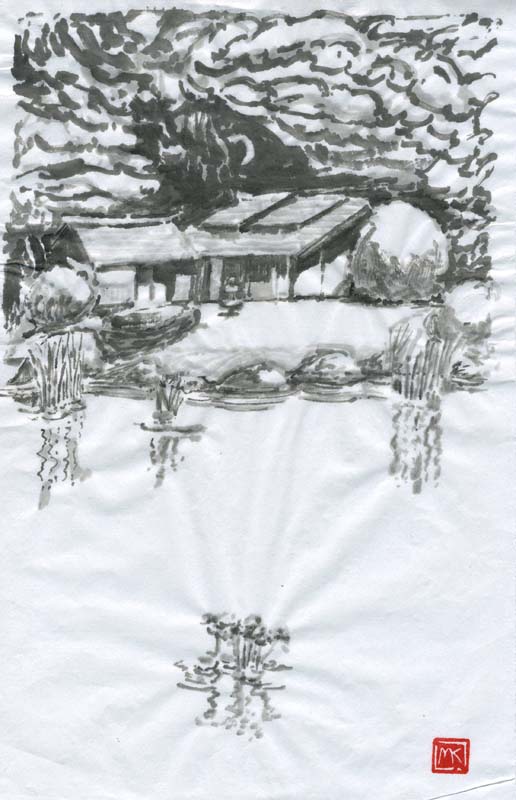

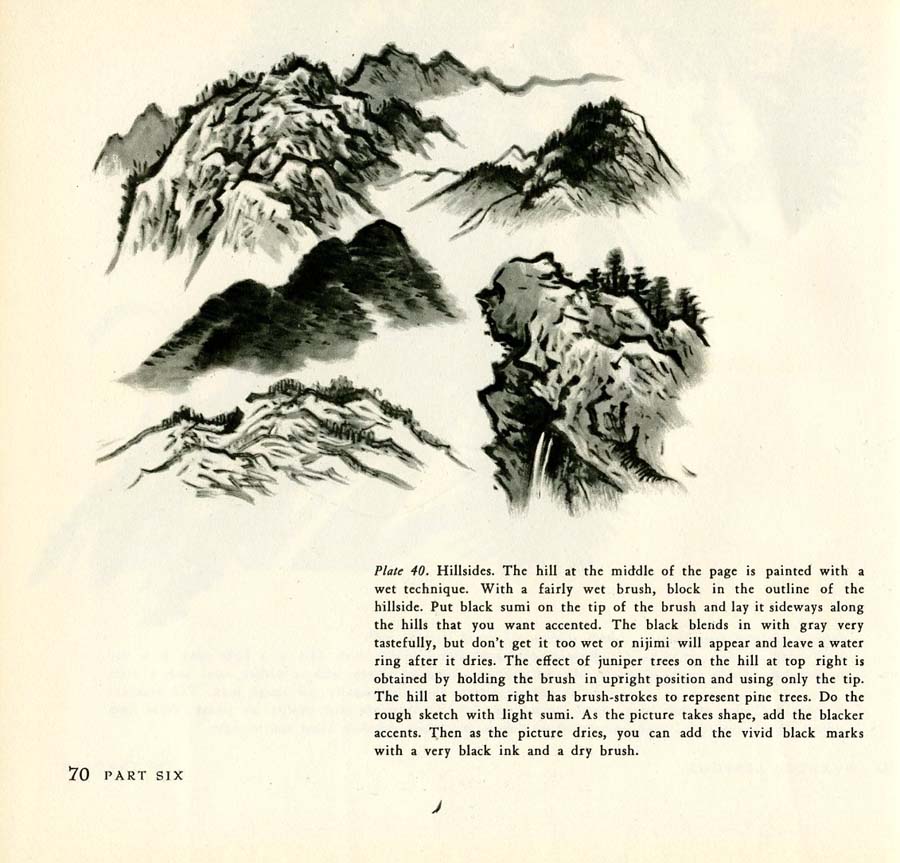

Mount Fuji. Prints by him and his imitators arrived in France in the Impressionist-Post Impressionist period late in the 19th century and had a huge impact on artists including Gauguin and Van Gogh: flat planes of colour, multi-point "free form" perspective and little if any atmospheric perspective. In France, a work of art became a surface rather than a window, and Western painting has never really looked back since. Traditional Japanese and Chinese painting is usually black and white and like Japanese society: ordered and precise with a set of values attached to every aspect of it, evolved out of "The Way" of Taoist Chinese philosophy ("Daoist" in pinyin). This is the bible: Note the Kenneth Rexroth quote on the back cover, written in 1956: "Nothing could be a better answer to the problems and dilemmas of modern abstract expressionism. Nothing could be a better antidote to the enervating poisons which have debilitated modern painting." It contains lists and aphorisms, such as "The Four Treasures: Brush, Ink, Inkstone, Paper," and statements like this at the beginning of a chapter called The Elements of a Picture: "Just as ceremonial rites and individual conduct in Chinese life were originally patterned on the order and harmony of nature, Tao, in the hope that a like order and harmony might prevail in society, so it has been in painting: the classification of subject matter, the codification of brushstrokes, the sets of rules and standards, and the self-cultivation required of a painter ..." This evidently is not artist-as-rogue-free-spirit as idealized in the West! My Japanese manual for sumi-e (literally ink-painting) is this, published in 1959: Suiboku means ink and water – thus the tones of grey that are different from the chiaroscuro black-white pictures I do that are like woodcuts.  Both books point out that the equipment is the same as used by a calligrapher/scholar: the Four Treasures mentioned above. "Writing a painting" is apparently an expression in China that also reflects the connection between calligraphy and art. Accordingly, I did a few calligraphy exercises with my friend Misako in Osaka, and wasn't very good at it. She takes a course with a master each week.  The typical traditional compositions, both of paintings and of gardens, were stacked arrangements of water, rocks and trees, sometimes containing distant figures and mountains. The foregrounds look exactly like Chinese and Japanese gardens, so which came first? It was the paintings, some of them nearly 1,000 years old, a wonderful example of life imitating art. There is very little spatial overlap. Layers of distant landscape are often separated by mist. I wondered whether part of the issue was the quality of the rice-based paper they used and its ability to hold tones without becoming murky. The author of the Japanese painting book was not very complimentary about Nijimi. These rings of dried ink when the paper gets too wet are sometimes referred to as "tidelines" or "explosions" in watercolour painting. I had this problem with the only painting on machine-made rice paper that I haven't thrown away yet, which I did on a bench at the Tokyo National Museum looking out onto its pond and tea house.  The paper wouldn't hold washes (but it would be okay for calligraphy). So I bought expensive hand-made washi, about $8 Canadian for a single sheet of about 20 x 30 inches. It was much thicker than the rice paper and held tones well, with interesting little imperfections that showed up as dots in the grey wash:  And, on the Noto Peninsula, found landscape that evoked everything I was seeing in Japanese gardens:  A personal thing is that I cannot paint or draw a picture without including or making up shadows or reflections. As David Hockney pointed out in his book Secret Knowledge, the Western art tradition is the only one in the world that uses shadows – he recorded a conversation with an Asian woman who, when asked why artists there didn't include shadows in their paintings, replied "they are not necessary." Here are a couple of other pages from the Japanese book:  With this kind of orthodoxy, where approval comes when artists mold their character after an idealized kind of Zen contemplation and their works are judged by their inclusion of classic elements and fealty to classic ideas of composition, it's no wonder so much of it looks the same. In this, it's a mirror of the society, where conformity has been prized. And the Japanese gardens we saw conformed as well – plants and layout varied only a little from tiny private gardens to large public ones. But the beauty of Japanese art and gardens is their meditative calm. It's the same with the Tea Ceremony: there is a way of doing it correctly, and you pause and think before beginning and at every step along the way. It's so different from the casual, do-as-you-please style of modern Western culture. |

Text & images © Michael Kluckner, 2019