Return to main Vanishing B.C. page Return to home page

Page last updated February 18, 2015

© Michael Kluckner

|

The BC Packers plant, company store and ancillary buildings on the Alert Bay waterfront, in the summer of 2002. The buildings were demolished in March, 2003. This was one of the last operating canneries in what had been in effect a company town. Surviving cannery museums elsewhere in BC are the North Pacific Cannery at Port Edward, south of Prince Rupert, and the Gulf of Georgia Cannery museum at Steveston (see also the Gold Seal Seafoods site) on the south arm of the Fraser River near Vancouver. The corporate predecessor to BC Packers began operation at Alert Bay in 1881, eleven years after the first store and saltery were established there. The complex was completed by the Second World War years. The cannery store also served as the post office after 1890, helping to establish consistent government services in the remote town. BC Packers had recently pulled out of the community leaving the buildings empty, but (as it has done in Steveston) has floated a number of proposals to redevelop the site and/or the buildings as a fishing resort or a conference centre. But I noted the following piece of news: "Minutes of the Council of the Village of Alert Bay, July 23, 2002: The Historic Alert Bay Development Corporation met with Sam Bawlf to discuss long-term economic plans for Alert Bay. They are to meet again in October 2002. A letter from the Corporation is being sent to B.C. Packers stating we are no longer interested in saving the building as B.C. Packers has failed to provide or be responsible for the clean up. B.C. Packers hired environmental engineers but refused to disclose the report. We would like them to tear it down and do proper reparation . . . ." Read a February, 2003 news story Written in 2002: My first impression of Alert Bay, compared with democratic Sointula (on nearby Malcolm Island) – where not even a church steeple punctuates the house rooflines – is that Alert Bay (on Cormorant Island) is a company or government town. The agencies of the state, including the church, the residential school [demolished in 2015 – see below], the hospital and the Big Employer, are all displayed prominently along the shore. There is also a fourth "state agency" – the 'Namgis First Nation with its U'mista Culture Centre and totem poles, including the tallest one in the world. Cormorant Island is divided between the Village of Alert Bay, about 100 hectares (230 acres) in extent, with the Alert Bay Indian Reserve occupying the balance. (There is another interesting BC Packers site, concerning the Boundary Bay Oyster Plant, at http://members.shaw.ca/j.a.brown/DeltaBCP.html) Note from Faye Kemmis (née Clelland), 2008: there were four major churches there; the Anglican one is the most decorative with a little steeple and is one of the oldest in BC; the Catholic one is small and was turned into a private dwelling; the lovely old log United Church where I was married to a Catholic as my Anglican church in 1970 banned me from marrying a divorced man; and the Pentecostal close to the Catholic church, all were very well attended when I lived there, from 1958 - 1970..travelling inbetween times. The Anglican one is over a hundred years old and now the Namgis First Nation fill it, and their language is used probably 90% of the time. Lovely memories and great culture. |

* * *

|

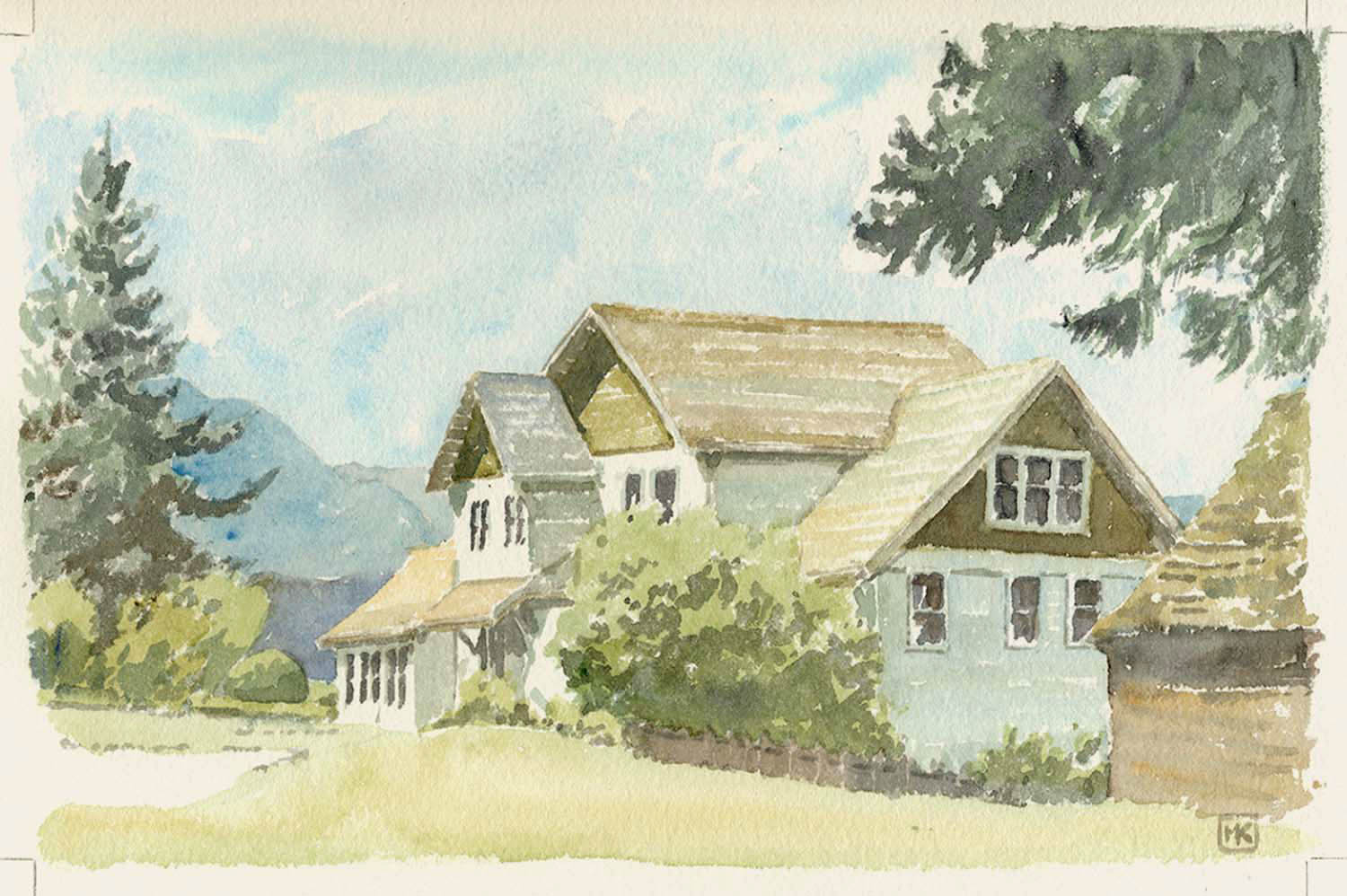

The nurses' residence at St. George's Hospital, Alert Bay. The two-story part was built in 1925 while the lower structure in the distance was added in 1941. In what was primarily an Anglican town, the first St. George's Hospital opened in 1909 and burned down in 1923. The hospital buildings still extant in the summer of 2002, behind the nurses residence (out of the picture on the left) are low, flat roofed structures with horizontal board siding and large, multipaned wooden windows--a style that reflects their parentage as an RCAF hospital from the Second World War (apparently originally located in Port Hardy and floated over--source: North Island Heritage Inventory and Evaluation (Insight Consultants, 1984), BC Heritage Branch Library, Victoria). Since the opening of the Cormorant Island Health Centre next to "St. Mike's" (below) these buildings have been abandoned. I'm unsure whether there is to be a new hospital built at Alert Bay, or whether the health centre is the permanent replacement for St. George's. St. Michael's Residential School ("St.

Mike's") |

|

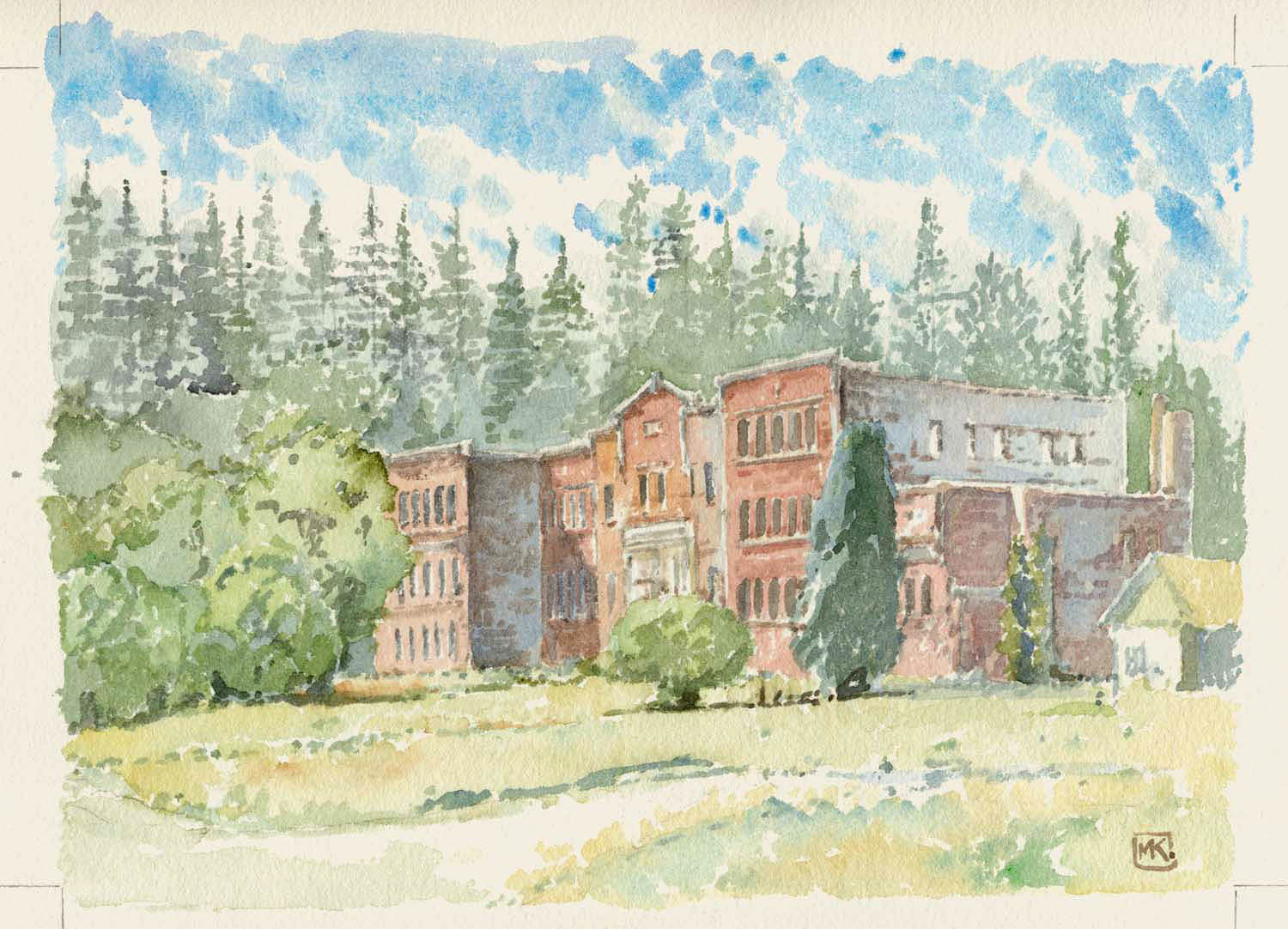

Written/sketched in 2002: The 'Namgis First Nation has owned the old St. Michael's Residential School since 1975, and still uses part of it for offices. In the Spring of 2003, it was renamed 'Namgis House (see news stories below). Built in 1929, it was one of a large number of residential schools in British Columbia (indeed, across western Canada) intended by the federal government and the churches to provide aboriginal children with a basic education as well as complete reprogramming from their parents' culture. Many of the residential schools were run by the Roman Catholic church, while others, including this one, were Anglican. Its style of architecture, brick colour and size cause it still to dominate the town--I mentioned above my impression, coming in on the ferry, of Alert Bay being a company or government town, and "St. Mike's" almost jumps off the landscape. It is set away from the commercial heart of the town, the part of the waterfront with the BC Packers plant, town hall and hospital, and until its closure in the early 1970s was more or less self-contained, with gardens, a dairy and an electrical generating plant. In front of it (to the left of the picture above) is the U'mista Cultural Centre, a museum of repatriated ceremonial regalia and "coppers" that commemorate the potlatch, one of the core aspects of traditional Kwakwaka'wakw culture. The banning of the potlatch by the federal government in 1884 was a significant attempt to assimilate the local people and destroy their culture. On the hill behind the residential school is the Alert Bay Big House, a traditional post-and-beam structure with its planked facade painted in traditional Kwakwaka'wakw designs. And, of course, there's the world's tallest totem pole nearby, all reasons why Alert Bay is an important stop on the cultural tourism circuit. Update, 2015: demolition of the school

began in mid-February with extensive news coverage, including

this excerpt from the Globe&Mail site: This brought to a conclusion a disagreement amongst members of the community about how or whether to memorialize the residential school experience there. For example, the Indian Residential School Resources website indicates, in an undated video, the desire of a chief who attended the school to keep it. Earlier stories, such as the ones below, talked of

a "new beginning." It is an interesting contrast with the St.

Eugene's Mission School near Cranbrook. Stories from North

Island Gazette, Port Hardy, thanks to Mark Allan,

publisher and editor

Regrettably, nothing of this scene survives, except for the church in the distance, which logically would be Christ Church (still a fixture of the waterfront but very altered from this picture). This part of the waterfront is pretty well cleared off, with the individual native families mainly living in standard government-issue houses on the streets on the hillside behind the residential school. Photographer unknown.

St. Michael's in the 1930s. The two-story wooden porch is gone now. Photographer unknown.

A 1940s photo by an unknown photogrrapher. The long building is the BC Packers plant, in the painting at the top of this page seen from the other side. Story from the North

Island Gazette, Port Hardy, pub’d February 5,

2003. (thanks to Mark Allan, publisher and editor) --------------------------------------- The information above specifically on Alert Bay buildings is largely gleaned from the pamphlet "Your guide to Historic Alert Bay," published in cooperation with the Alert Bay Museum and Library. Its website is available from the BC History Internet/Web Site. Additional information from North Island Heritage Inventory and Evaluation (Insight Consultants, 1984), BC Heritage Branch Library, Victoria.

|