|

The book poster that was so popular -- we didn't use it as a cover image because we on the Left Coast felt it was too Ontario-centric. Pity. |

|

The book poster that was so popular -- we didn't use it as a cover image because we on the Left Coast felt it was too Ontario-centric. Pity. |

Return to main travel page Return to home page

" . . . Then came the Québec

sovereignty referendum of 1995. The Québec government, who

are masters

at the Identity Game, had been working for decades preserving monuments

and retaining and developing an encoded, magical landscape, redolent of

myth and legend, of ancient settlement and the changing seasons, of

roots and history, of the warmth of home and the deep snows of winter.

The federal government's response, coordinated by the Deartment of

Canadian Heritage, was to give away more than $20 million worth of

Canadian flags, without any corresponding discount or tax rebate on

flagpoles. They might as well have been grabbing at smoke. " . . . Then came the Québec

sovereignty referendum of 1995. The Québec government, who

are masters

at the Identity Game, had been working for decades preserving monuments

and retaining and developing an encoded, magical landscape, redolent of

myth and legend, of ancient settlement and the changing seasons, of

roots and history, of the warmth of home and the deep snows of winter.

The federal government's response, coordinated by the Deartment of

Canadian Heritage, was to give away more than $20 million worth of

Canadian flags, without any corresponding discount or tax rebate on

flagpoles. They might as well have been grabbing at smoke.

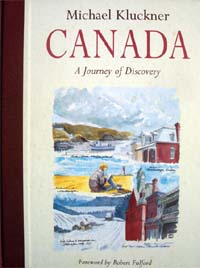

"In the aftermath of that referendum, I decided to see if my encoded Canadian landscape, cobbled together from the symbols, images and imaginings of my youth, actually existed. Was this dreamscape mere make-believe? Had economic and social change caused it to fade, while new development homogenized it, so that every part of the country looked like every other part? Had Canada become a virtual country, held together only by emotions and abstractions?" --"In Search of Canada" (Chapter 1) Left: a man somewhere in the Maritimes with a sign describing the pace of his life. In the old saying, if you want to be successful in politics in the Maritimes, you pave it if it doesn't move, pension it if it does.(Under the heading "Notes from the Road," the book proceeds across the country, more or less from east to west, following the sun, examining the built heritage and landscapes that comprise my image of Canada. The book ends with a chapter entitled "The Quest for a National Trust," describing the efforts to create a body that would act as a steward of the country's heritage. The book is long out of print but can be found quite easily on used-book sites. See my books page for further information.) |

|

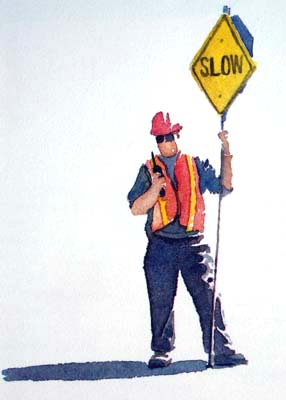

Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia, serene and blue in the October sunshine. "Our main export is our children," said a friend who had grown up in Nova Scotia. She had left, too, following marriage to a navy man in Halifax and a transfer to the West Coast, but she still missed the friendliness of the Maritimers, their lack of the sort of keeping-up-with-the-Joneses materialism she saw all around her in British Columbia. "The sea holds back the arrival of winter," she told me, "but it also holds back the arrival of spring."I'll go in October, I thought, to see the fall colours, and I won't have to take a snow shovel as carry-on baggage. |

|

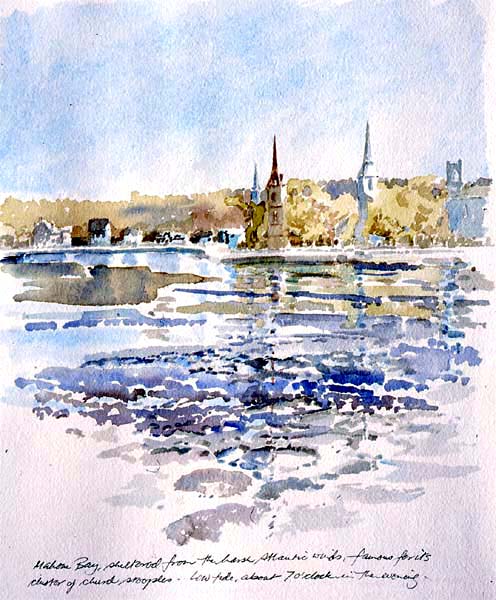

Mahone Bay, in a sheltered Nova Scotia cove not far from the rocky, wind-blown Peggy's Cove. You look at this and you think, "that's a New England landscape," reflecting how dominant American images are in the culture. And it is from that era -- the colonial one, reflecting the common values that run along the Atlantic coast regardless of the international boundary. |

|

Old cafe in Saint John, New Brunswick, with pressed-tin ceiling. The only place (other than Tim Hortons) open Sunday morning.

June 16, 1997, back at home, working on these paintings, when an item came on the CBC radio: the Crown Prince of Jordan and his wife were unexpected arrivals at Saint John airport due to airplane engine problems. The mayor and his wife dropped everything and headed out to the airport in their station wagon to meet them. There was no protocol arranged, of course. The reporter asked the mayor: "So what did you do to entertain the royal couple?" "Well," he replied, "we took them to Tim Horton's! Where else would you take somebody from out of town?" Apparently, for the mayor, the finest asset in his historic city is a franchise of a national doughnut operation! |

|

|

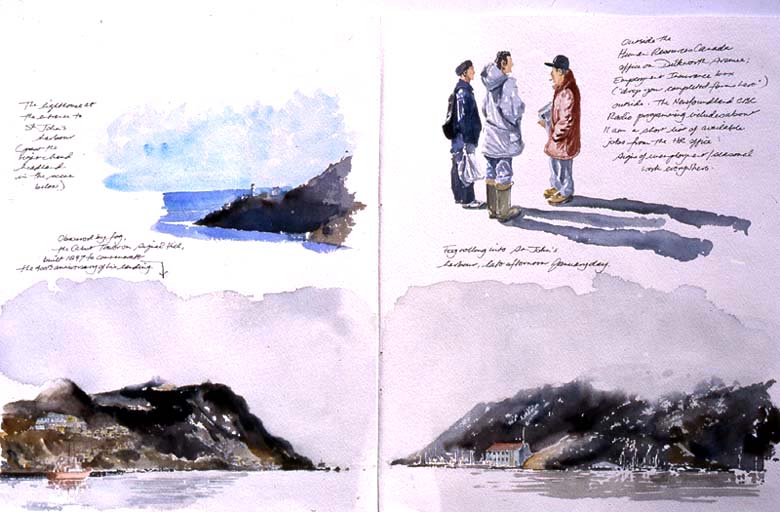

The

lighthouse at the

narrows of St. John's harbour, Newfoundland, on a bright February

morning (above) and later in the day when the fog rolled in and chilled

the colours to greys and sepias.

After a late-night arrival at the St. John's airport: ". . . Marks t'harbour entrance," the cabbie remarked, looking at the light flashing in the blackness. He paused a minute, listening to the crackling conversation on the radio. "I'll prab'ly be busy again in about 'alf an hour." "At this time of night?" I asked, surprised. "Another flight trying to come in?" "Bars'll close," he replied, gesturing to his left toward a block of low buildings. "T'at's George Street. Every building's a bar, and t'ey don't close till tree." |

|

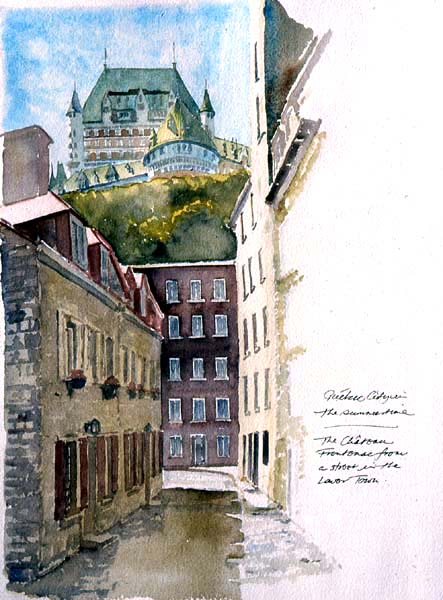

The

Chateau Frontenac on the ramparts above Québec City's old

town: a fantasy of a Loire chateau sketched by an American (WC Van

Horne, the general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway), designed

by a New York architect (Bruce Price of the firm McKim, Mead and

White), and built to enhance tourism in a conquered French colony. And in a further twist, its chateau style becomes the default design for railway hotels all across the country, adopted by the Canadian National and Grand Trunk railways, so it became one of the few national architectural emblems. |

| An

odalisque in the park at Riviere-du-Loup, where the ferry crosses the

St. Lawrence River, on a sweltering day in July Early the following

year, on a winter trip, I arrived at

the Hotel Chapeau on the Ile aux Allumettes in the Outaouais: Cheery

tavern, good dining room

and, uh, spartan accommodation for the wandering artist. The only

non-sociable people in the tavern are the Video-Lotto

players -- transfixed, they sit so still and are very easy to draw.

Outside it had begun to snow. The bartender came over. "Pareil?" he gestured at my glass. I said no, and then, without really thinking about what I was doing, asked him if he rented rooms. "Sure," he said (en francais), "gotta nice one on the back corner." "How much?" "Go see it first." He handed me a key and directed me up the stairs and around a couple of corners to Room 14. I swung the door open, found the light switch and flipped on a bare bulb hanging by its electrical cord from the ceiling; a narrow cot with patched blankets and darned sheets stood in one corner, a small dresser and a chair in the other. There were windows on two sides that looked out onto the village in the valley below, now obscured by the blowing snow and the rapidly fading light. I descended the stairs and went back into the tavern. "What'd you think?" the bartender asked. "Well . . . how much is it?" "Twelve dollars a night." I took it. |

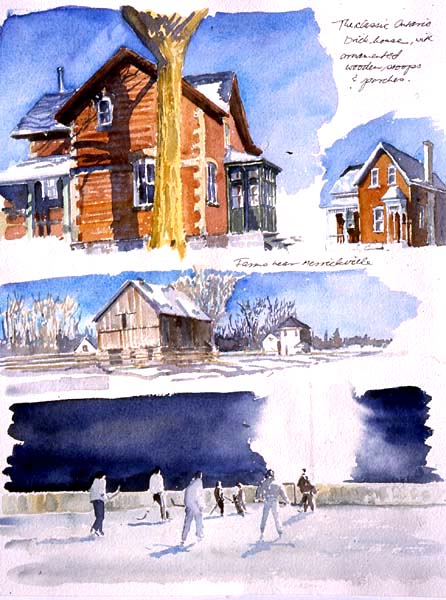

| A winter trip to the towns west of Ottawa in the cold winter of cobalt skies and long purple shadows. Went out walking one evening in Merrickville, on a night so cold the snow squeaked under my shoes. In the distance I could hear the shouts and cracks of sticks on pucks of a hockey game. On an outdoor rink, under the glaring lights, a spirited pick-up game animated the endless winter night, and I thought about Canada, the peace-loving nation with the most violent national game in the world. |

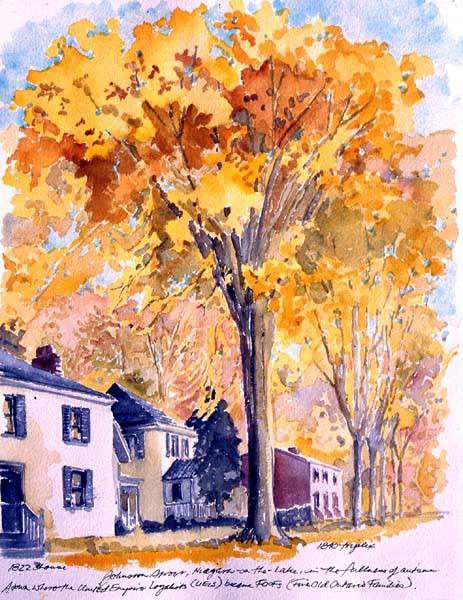

| Niagara-on-the-Lake, sometimes called NOTL, has streets of splendid trees and colonial houses. It is the part of the country most significant to the (unsuccessful) American invasion during the war of 1812. This is where the UELs (United Empire Loyalists) from the post-revolutionary period evolved into the FOOFs (Fine Old Ontario Families), the bastions of Ontario conservatism and upholders, they believe, of true Canadian values. Because so much of the Canadian publishing industry was headquartered nearby in Toronto, home of the colour Sunday supplements such as the Star Weekly magazine, I grew up believing that this is what Canada was supposed to look like. Where we lived, out on the Wet Coast, it was of course very different, leaving me feeling slightly unhinged from the Canadian mainstream. |

|

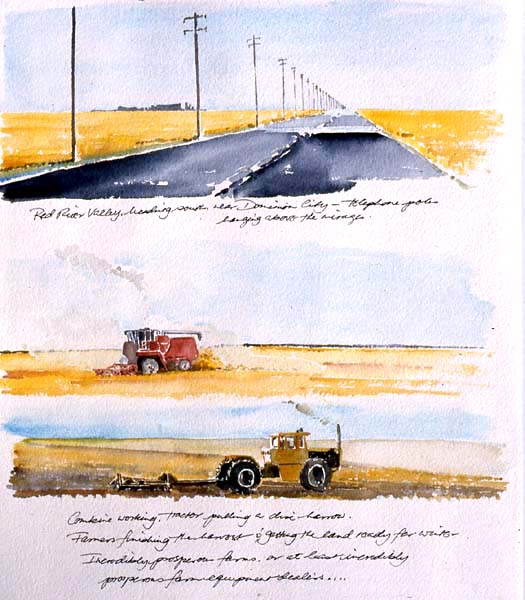

Images from the Prairies -- a flat land and a rigid grid. |

|

The

northern, "Parklands" stretch of the Prairies along the Canadian

National rail line passes dozens, if not hundreds, of almost-abandoned

single-elevator towns. The wooden elevators stand up above the prairie

grasses like lighthouses above the low Atlantic coastline. But they're

hardly a beacon anymore, as settlement has consolidated into the

one-in-six, one-in-ten towns that have amalgamated government services.

In the 10 years since 1997 when I painted this elevator near Ranfurly,

east of Edmonton, hundreds of these elevators have been demolished.

It's like what people say about Venice: if you want to see it, go now. On the radio while sitting on the roadside painting, I heard a song by the band Prairie Oyster, with the refrain: "Every train that's leavin' a prairie town / Is runnin' on a one-way track." |

|

Late summer thunderstorm in central Alberta. The sort of landscape where, as in the old saying, you can watch a dog running away for two days. |

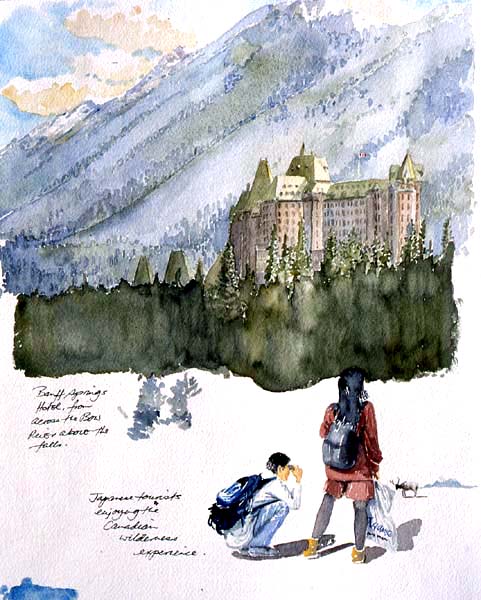

| The wonderful Banff Springs Hotel, a castle as grand as any in the world, above the Bow River. It's the successor to Québec's Chateau Frontenac above. On this visit there, in 1997, the Rocky Mountains were overrun with wealthy young Japanese tourists.... |  |

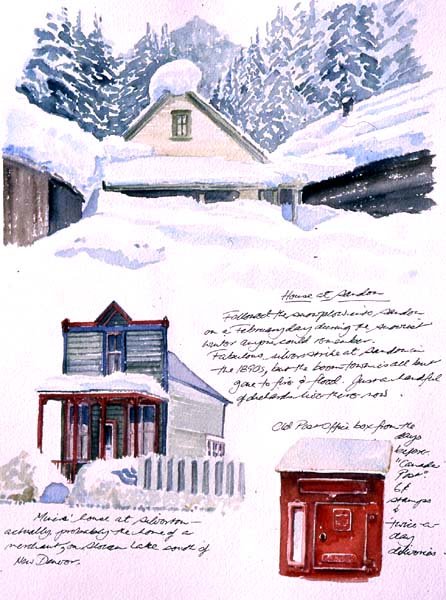

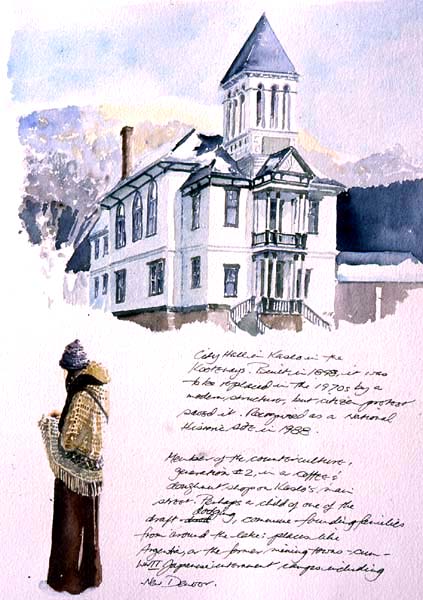

| I went exploring

in the Kootenays in southeastern British Columbia during the especially

snowy winter of 1998. These were the pages from the BC part of the book

that I liked the most, perhaps. On my later, Vanishing British Columbia project, I returned to Sandon to paint and wrote a lot about its complex, troubled history. |

|

| Kaslo on Kootenay Lake is the old supply centre for the Kootenay mines nearby in Sandon. It is now well into its second generation of the '60s counterculture. |  |

Return to main travel page Return to home page