Text & artwork © Michael Kluckner, 2009

Contact me Return to home page

|

|

|

|

|

| D Daggy: bad or "crap." A dag, in its original meaning, is a "bell" of poo-encrusted wool dangling down the backside of a sheep that needs to be drenched – i.e. wormed. So a daggy sheep is not such a good one; ditto for a daggy town or daggy clothes or whatever. Debut: pronounced "day-boo" in Australia. With a full Australian accent, it's "die-boo." Dob in: to turn someone over to the authorities; to rat or fink on someone. On the Australian immigration website, for example, there is a "dob in" link for catching cheaters and other illegals. Donga: a prefabricated or makeshift building usually set on a treeless, arid plot of land under a beating sun. The sort of accommodation you might get if you give up trying to afford a city lifestyle and head out to WA to participate in the mining boom. Drizabone: the iconic Aussie stockman's coat, made of thick oiled cotton and weighing about as much as a sack of beer when dry, even more when wet. It is very distinctive with its wide epaulets, like a tent fly, to shed the rain. To complete the costume, wear an Akubra hat, elastic-sided boots and beige moleskin trousers, but never within a day's drive of any major city unless it's Easter-show week. Drongo: a yobbo. From Elizabeth: as well as drongo, there is "dill brain" =stupid, sometimes just referred to as "dill." Duco: the paint-job on a car. E EFTPOS: a debit-card system – at least that's what it would be called in the States. So if a business has EFTPOS you can use your bank card for a direct withdrawal. It must mean something like "electronic funds transfer possibly." Esky: the portable cooler that's an essential part of Australian summer recreation. Esky is a brand, derived from “Eskimo,” but the term has become a generic like Kleenex or biro – applied to any cooler you'd take to the beach. In the Australian pantheon, the God of Refrigeration has his own special niche. Unlike in Europe and North America, there was no possibility of ice-harvesting so food preservation was almost impossible. Necessity being the mother of invention, a Scottish-born journalist and tinkerer named James Harrison designed the world’s first ice-making plant at Geelong, Victoria, in the 1850s. His first client was a brewery in Bendigo, then in the midst of the Gold Rush. His efforts in the 1870s to develop refrigerated ship chambers spurred the development of the country’s hugely significant meat-export business. Source: http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A010479b.htm  Expats:

you’ll read and hear a lot about expatriates –

Australians who have gone Overseas

for educational or career opportunities or who have fallen in love with

a foreigner. In the old sense of the word, people who moved away

– often to London, it seemed – were fish too big

for Australia’s small pond, artists and writers seeking a

wider world and an escape from the perceived provincialism of the

Antipodes. Writing in 1965 of artists in the “Frustrated

Fifties,” George Johnston suggested that “some

measure of detachment or removal from Australia, for a few years or for

many, is organic to full Australian creative development.” (p.

208) Expats:

you’ll read and hear a lot about expatriates –

Australians who have gone Overseas

for educational or career opportunities or who have fallen in love with

a foreigner. In the old sense of the word, people who moved away

– often to London, it seemed – were fish too big

for Australia’s small pond, artists and writers seeking a

wider world and an escape from the perceived provincialism of the

Antipodes. Writing in 1965 of artists in the “Frustrated

Fifties,” George Johnston suggested that “some

measure of detachment or removal from Australia, for a few years or for

many, is organic to full Australian creative development.” (p.

208)So the Robert Hugheses, Germaine Greers, Clive Jameses and Sidney Nolans of the arts world, the Peter Finches, Leo McKerns, Mel Gibsons and Russell Crowes of film, were reflecting the Culture Cringe while wanting to swim in the pond with the biggest sharks. If they came back and deigned to criticise their homeland, as Germaine Greer is wont to do, they were treated as Tall Poppies and savagely rebuked. With the globalisation of the Australian economy and the transferability of professional qualifications, there are now mobs of “non-artistic” expats working in finance in New York, teaching in Dubai and otherwise getting “overseas experience” – the skills Australia needs to keep up! And move the country forward into a bright and prosperous future!! And what of this expat life? Englishman Jonathan Raban, reflecting on his years in the USA, wrote that “what seemed charming and novel to you as a visitor can quickly tire when you’re a lifetime resident … The longer one stays, the more jarring are these reminders of one’s uprootedness: just when you’re feeling most at home, an encounter at a supermarket checkout or an exchange at the dinner table confronts you with the bleak fact that you’re a stranger here.” (NY Review of Books, 25 Sept 2008 p. 70) Which of course applies to many newcomers to Australia. Expect to be called a tourist, even after years of residence. F Fair go: Not a shortened way of saying “I’m off to the exhibition,” but one of the fundamental tenets of Australian society. It not only means that everybody should have an equal chance to get a job or make a living, but that the government-mandated “minimum award” or wage and benefit package should be enough to support an acceptable standard of living. The “working poor” so prevalent in the USA, for example – those working multiple jobs but still unable to feed, clothe and shelter their families – don’t exist to the same extent here. Instead there are “working families” – the mythic bedrock of the nation invoked by politicians of all stripes and relentlessly bribed with handouts as election time approaches. Fall: What you do when you're trying to walk home from the pub. The season during which the leaves of exotic, northern hemisphere trees change colour, when the native grey-green gums turn slightly greyer, is called autumn.  Ferals: any

people who look different from the norm, but especially

referring to members of the wilfully poor and the downwardly mobile.

Edgy inner-city suburbs have "gone feral," according to middle-class

observers. The usual feral costume includes piercings, head lice,

dreads (dreadlocks) or a faux-hawk, tats, a T-shirt with an aggressive

slogan and ripped jeans. Old-fashioned hippies might be described as

feral, too, because they're different.

Poor people's cars or utes

can

also be described as feral. And of course the word in its original

meaning describes the millions of cats, dogs, toads, donkeys and camels

that have gone wild in the past 200 years and are gradually

obliterating the nation’s native flora and fauna. Ferals: any

people who look different from the norm, but especially

referring to members of the wilfully poor and the downwardly mobile.

Edgy inner-city suburbs have "gone feral," according to middle-class

observers. The usual feral costume includes piercings, head lice,

dreads (dreadlocks) or a faux-hawk, tats, a T-shirt with an aggressive

slogan and ripped jeans. Old-fashioned hippies might be described as

feral, too, because they're different.

Poor people's cars or utes

can

also be described as feral. And of course the word in its original

meaning describes the millions of cats, dogs, toads, donkeys and camels

that have gone wild in the past 200 years and are gradually

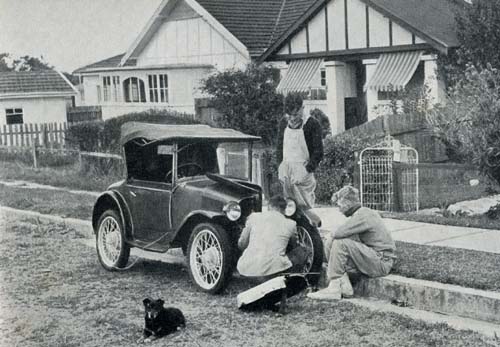

obliterating the nation’s native flora and fauna. 1937

newspaper ad, Sydney Herald.

Fibro: the cheap, all-purpose sheets of building material that democratised the nation’s mountain and beach cottages and, due to its asbestos content (before the 1980s), killed thousands of Australians. Fibro-sheathed houses are quite safe as long as you keep them painted and don't try to saw them, drill them, or hammer things into them, and you leave town if one of them is being demolished nearby. The Fibro sheets for sale now are fibrous cement without any asbestos content. Fine: in weather reports, a forecast that it isn't going to rain, which does not necessarily mean that it will be sunny.  Flag:

the national

one is the Australian ensign with the Southern Cross

to the right, the Federation star below and the Union Jack of Great

Britain in the top left corner, an irrefutable colonial link to Mother

England in spite of a century of self-government and two generations of

republican rumblings. It is an ensign, like the one flown in all the

dominions, such as in Canada until 1965. Flag:

the national

one is the Australian ensign with the Southern Cross

to the right, the Federation star below and the Union Jack of Great

Britain in the top left corner, an irrefutable colonial link to Mother

England in spite of a century of self-government and two generations of

republican rumblings. It is an ensign, like the one flown in all the

dominions, such as in Canada until 1965. One of the impediments to a distinctly Australian flag is the retired military, represented by the Returned and Services League (RSL), who fought under the ensign; the other is Australians for Constitutional Monarchy, perhaps the most organised of the anti-republican groups, who believe that the flag must show the nation's (British) cultural heritage. The most distinctively Australian flag is the Aboriginal one, below.  The official flag may be red, white and true blue but the country’s official colours, mainly seen on sports uniforms, have been green and gold since a vice-regal proclamation in 1984 (thus, the colours I've used in the page header above). It is a combination better suited to a doorman’s uniform at a large Third-World hotel. The justification is that the colours mimic those of the golden wattle, the country’s floral emblem, which itself clashes terribly with the muted olives and greys of the Australian bush and should be dug out and eradicated. Flies: "I came back to Australia after a few years away and was walking out of the airport into the sunshine. Up ahead was a man in a white shirt, the back covered with black dots. I'd forgotten about the flies." – Christine  The two main types are the blowies (blow flies) that make indoor life miserable and are maggot-filled, despoiling food and leaving a gross mess when you whack them, and the bush flies that make outdoor life miserable by sticking to your face, trying to crawl into your eyes and mouth and yet being so quick you can never swat them. The only positive thing you can say is that the latter won’t follow you and the blowies indoors. The number of bush flies, especially in the spring, forces people to do the “Australian wave” – moving the hand rapidly back and forth in front of the face to try to bat them away. However, Australians can feel smug that, although they have lots of flies, neither of the main types are biters like the horrid black flies that make springtime in eastern North America a misery.  The venerable Mortein company, whose 1930s ad is reproduced above, created an anthem in the 1950s with its Louie the Fly song. “I’m Louie the Fly, Louie the Fly, straight from garbage tip to you, I’m bad and mean and mighty unclean,” it goes, ending with the slogan, “Afraid of no-one, ‘cept the man with the can of Mortein!” It is said that children of that era could all sing that song, the Aeroplane Jelly Song and the Vegemite Song the way previous generations knew the words to “Jerusalem” and “God Save the King.”  Flip-flops

(aka thongs until that became the word for a piece of

women's underwear): required footwear for the Great Australian Waddle.

This is the summertime walk of the shopping malls, in which the body

leans back slightly, allowing each leg in turn to extend in front, the

foot angled to the side and placed on the ground with a slapping sound,

creating a slow rocking movement in a forward direction. The arms

dangle, or perhaps move slowly forward and back as if imitating a

normal walk, unless loaded with packages. It is performed most

effectively by the obese. Knee-length shorts and long, untucked

T-shirts give a tubular shape to the body and complete the ensemble. No

one has yet managed to walk backwards successfully in flip-flops. Flip-flops

(aka thongs until that became the word for a piece of

women's underwear): required footwear for the Great Australian Waddle.

This is the summertime walk of the shopping malls, in which the body

leans back slightly, allowing each leg in turn to extend in front, the

foot angled to the side and placed on the ground with a slapping sound,

creating a slow rocking movement in a forward direction. The arms

dangle, or perhaps move slowly forward and back as if imitating a

normal walk, unless loaded with packages. It is performed most

effectively by the obese. Knee-length shorts and long, untucked

T-shirts give a tubular shape to the body and complete the ensemble. No

one has yet managed to walk backwards successfully in flip-flops.Fluoros: the polyester shirts and vests, lemon-yellow on the top half and black below, now favoured as a uniform by workmen, tradesmen and truck drivers, whether public employees or not. A variation is an attractive orange and black model. An advantage to wearing them is that they cover a lot more skin and thus reduce the chance of skin cancer compared with the Chesty Bond type singlets of an earlier era. |

People living in Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and the Northern Territory usually watch “Aussie Rules,“ the footie of the Australian Football League. It’s the locally developed game, begun in the 1860s in Melbourne, with four goalposts (no crossbars) and typical game scores up into the three digits, like basketball. New South Wales and Queensland residents usually refer to National Rugby League games when they talk about footie. It’s the professional version of the classic English game, with the two goalposts and crossbar. There are 15 NRL teams. It and its AFL cousin are about as violent as a game without sticks and skates can get. Easy to understand, though, compared with, say, cricket. The “amateur” version of NRL is Rugby Union, which plays internationally under the banner of the Wallabies. And finally, there’s Football Federation Australia (formerly Soccer Australia), which plays football aka soccer and whose team, the Socceroos, competes internationally. Rugby Union is the posh or "toffy nose" game, played in private schools and considered to be a stepping stone to one's later career (in law, business, fleecing widows?), whereas League is working class. To the uninitiated the games look the same, but it's an interesting window into the subtleties of the Australian class system. Johnston’s assertion from four decades ago about “fervent” support is beginning to ring a bit hollow, as a number of the NRL teams are said to be in financial trouble. The recent antics of NRL players – sexual scandals, arrests, fights and drunkeness – have put that game into the news news as often as in the sports news. www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/football/ 4WDs: Four-wheel Drives, the usual Australian term for American-style Sport Utility Vehicles as well as the more rugged Land Rover-type of off-road country vehicles. Many are fitted with snorkel air-intakes to grab clean air from above the dust storm created by rampaging across a piece of fragile native ecosystem. As a rule, the narrower and trendier the inner-city street, the higher the number of wide, snorkel-fitted 4WDs.  Frock: The wonderful old word for a dress, still very much in use in Australia, as are the frocks themselves, perfect for a hot day. G Galah: the common pink and grey parrot that is a synonym for stupidity. Gallipoli: the foreign site that is sacred soil to Australians. It is in the Dardanelles on the Turkish coast, where the ANZACs landed on April 25, 1915 and faced a crushing defeat, during which the soldiers demonstrated incredible individual valour and loyalty in spite of the incompetence of their leadership and the overwhelming strategic superiority of the Turkish position. Newcomers to Australia sometimes have difficulty understanding the "cult" of Gallipoli, why it is so universally known whereas other Australian military episodes – including even bloodier defeats (Fromelles) and glorious victories (Le Hamel) in France during WWI and in Asia (the Kokoda Track) in WWII – are not part of the general public consciousness. Is it because it was the first engagement of the ANZACs? Is it because the flower of Australian youth was so callously sacrificed by foreign (that is, Pommy) officers and politicians, especially Winston Churchill who is equally loathed for his unwillingness to defend Australia with British troops and ships in WWII? Because the ANZACs were underdog battlers and it played into the legend – like Ned Kelly or the defenders of the Eureka Stockade during the Gold Rush – of Australians as defiant victims? All good questions, all fodder for the creation of a national identity. Gazump: to be beaten out for something such as an auction. You get gazumped if your highest bid at, say, a house auction (where most houses are sold in hot markets like Sydney) isn't high enough.  Gold:

the second

great discovery in Australia's settlement history (the

first was the merino sheep). Gold:

the second

great discovery in Australia's settlement history (the

first was the merino sheep).The convict era was winding down and the colonies that occupied the edges of the continent were slumbering along in the sunshine when gold was discovered near Bathurst in New South Wales in 1851. As historian John Maxwell Freeland put it, “The Society, nicely ordered on traditional lines into an upper landed-gentry class and a mass of illiterate workers, was at first leveled and then upturned in a sudden revolution.” No sooner had the mob headed for central New South Wales than even richer strikes were made at Ballarat and Bendigo in the newly established colony of Victoria. Freeland continued: “The effects of gold reached into every nook and cranny of the country. The total fabric of society was twisted, changed and altered as the gold flowed out. Politics saw the flowering of new liberal and radical philosophies, the abolition of property qualifications for members of the Assembly and manhood suffrage [female suffrage began at Federation in 1901, earlier than that in South Australia] … The old class order disintegrated. The selfish throttlehold of the powerful landed gentry was broken. The squattocracy was replaced by a new bourgeoisie having its strength in commerce.” California’s Gold Rush had begun two years before Australia’s, in 1849; many of the miners who had arrived too late there boarded ships for Sydney and Melbourne. Further rich strikes drew adventurers from all over the world back to North America in the late 1850s, to the interior of British Columbia, then further north in the 1890s to the Klondike. So what was the legacy of this mother lode on the Australian landscape? There are “ghost towns” including Sofala and Hill End in New South Wales, which have their parallels in Virginia City, Nevada, or Barkerville, British Columbia. On the west coast of North America, gold rush money did trickle into the big cities: San Francisco developed some fine buildings, a few of which survived the 1906 earthquake, as did Seattle and Vancouver due to their roles as supply points for the Klondike. But Australian cities, especially Melbourne, Ballarat and Bendigo, benefited permanently, the money sticking around and paying for grand, fine architecture. Melbourne more than makes up for its dull setting by this graceful urbanity, and it can thank the gold rush for that. Grey nomads: not the picturesque roos of the countryside, but the picturesque seniors in their camper-vans or “poofter vans” (because there’s an entry at the rear) or towing their caravans, rambling around seeing Australia after decades of nose-to-the-grindstone labour and family-raising. Their migratory routes, visible from outer space, are north and west toward the Outback and the Top End in June as the weather cools, reversing as spring begins. From Elizabeth: Tim Winton in his book Dirt Music set in WA uses SADS = seniors approaching death syndrome for the hordes of seniors in camper vans driving around Australia – maybe it's a WA term? Gum: a) the substance on your knee after a trip by public transit. b) the monosyllable referring to the eucalyptus tree in all its myriad species. The iconic shape in the Australian landscape. It is Australia's gift to California and southern France, where it has become a weed, supplanting native species the way the radiata pine has invaded the Australian bush. H Happy Clappers: members of an evangelical church. Hessian: burlap.  Hill's Hoist: as a

rotary clothes line it is not unique to Australia,

but its raising and lowering mechanism, operated by a crank and

invented by Lance Hill in Adelaide in 1945, makes it more useful than

most. In a world of "advanced countries" where laundry lines are

shunned and energy-wasting clothes dryers are almost universal, the

Australian Hill's Hoist is everywhere. Yes, it's sunny a lot of the

time, but still ... According to Wikipedia, "it is considered one of

Australia's most recognisable icons, and is used frequently by artists

as a metaphor for Australian suburbia in the 1950s and '60s." Hill's Hoist: as a

rotary clothes line it is not unique to Australia,

but its raising and lowering mechanism, operated by a crank and

invented by Lance Hill in Adelaide in 1945, makes it more useful than

most. In a world of "advanced countries" where laundry lines are

shunned and energy-wasting clothes dryers are almost universal, the

Australian Hill's Hoist is everywhere. Yes, it's sunny a lot of the

time, but still ... According to Wikipedia, "it is considered one of

Australia's most recognisable icons, and is used frequently by artists

as a metaphor for Australian suburbia in the 1950s and '60s."Home Unit: a self-owned flat, what would be called a condo in North America. Hoon: the reckless-driving law-defying politeness-disdaining alcohol-binging delinquent young sociopathic outlaw, most common in the mortgage-belt suburbs around major cities. "Wedoanhefenuftado," they explain as justification for their hooning. What's a hooniform? A hoody, sunglasses, sneakers, torn jeans. The equivalent term elsewhere might be punk, JD, hood, greaser… Houses: the shelters that began as a direct response to the harshness of the climate; then, as the colonies settled, they reflected the fashions of the age, for better or worse. According to an article in The Australian, your home is no longer just a pile of bricks, it's a lifestyle statement. Mine says we’re poor and struggling, how about yours? One curiosity is the very common naming of houses, with plaques often visible from the street. A lot of the names seem to have Aboriginal roots, but there are clever (?) ones such as Linga Longa, a holiday cottage in Katoomba. From Elizabeth: as an example of letter reversal, EMOH RUO was a popular house name on inner city houses in Sydney. Most early Australian houses were bungalows – that is, single-storey – without basements, easy to build and sprawling across the large lots. Many of the modern McMansions have second storeys like North American and British houses. Basements are very uncommon compared with North America.  The suburban dreamscape, a 1950s photo probably by Bernd Lohse. The Aussie intelligentsia generally bemoan the lack of, they claim, a distinctive residential architecture – of anything of value in the suburban dreamscape, while focusing their wrath on the sprawl of the cities. Often they become almost feverish at the sight of roofs from (departing?) airplanes, “the red tiles mostly and red brick, ranging from the ruddy through the liverish to the apoplectic,” (George Johnston). Freeland quote: “…” The architect and critic Robin Boyd (part of the renowned family of artists) was at his most scathing in The Australian Ugliness, published in 1960. “The Australian town-dweller spent a century in the acquisition of his toy: an emasculated garden, a five-roomed cottage of his very own, different from its neighbours by a minor contortion of window or porch – its difference significant to no one but himself. He skimped and saved for it, and fought two World Wars with it figuring prominently in the back of his mind. Whenever an Australian boy spoke to an Australian girl of marriage, he meant, and she understood him to mean, a life in a five-room house.”  1930s

soap advertisement

Boyd’s principal target was the ranchers of the outer suburbs, an adoption after WWII of the worst of American bungalow-building and a colossal error given the harshness of the Australian climate. With their narrow eaves, lack of porches and ugly, unarticulated facades, they’re a blot on the landscape, no question. Is it any surprise that the average Australian house, now “needing” air-conditioning due to their inappropriate designs, consumes nearly two-thirds more energy than one did a generation ago? And to make matters worse, in the decades since Boyd launched his screed the new houses in outer outer suburbs have become as awful, as overblown, as the “dream homes” of North American streets. Two-storey, double-height entryway, grand McMansions. Arghhhhh… To foreign eyes including mine, Australia has distinctive, handsome houses, a great diversity of interesting urban terraces, classic garden suburbs, and traditional rural homes beautifully adapted to the climate. It’s like with the shopping villages – you have to be from somewhere else, perhaps, to appreciate how good they are, how well they are tied in to walkable towns linked by transit. Australian suburbs look different, attractively so, and stand up to anything in North America and Britain. |

|

|

|

|

|

Contact me Return to home page