Text & artwork © Michael Kluckner, 2009

Contact me Return to home page

|

|

|

|

|

| N National Anthem:"Advance Australia Fair," first performed in 1878 but not declared the national anthem until it dethroned "God Save the Queen" in 1984. The fourth line of the lyrics is the easiest to remember – "our home is girt by sea" (a rare opportunity to use the word "girt") – and the melody is hard to get right, especially when one realises that the lyrics can be sung to the impossible-to-forget "Gilligan's Island" tune. The best time to try to learn the anthem is during the Olympics, when it’s played constantly due to all the Aussie gold medals. In the 1977 referendum to choose the national song, "Waltzing Matilda" (see Swag), much easier to sing and with a more joyous refrain, placed second.  Ned Kelly mailbox near Cullen Bullen, NSW. Photo by Christine. "No worries": the universal way of saying "you're welcome," in response to an expression of thanks, but also as a response to "goodbye," or used practically anywhere else in modern conversation. As an Attitude, it fits in with “she’ll be right.” Like “mate,” its use is in inverse proportion to the distance from the centre of a big city. O  Outback: the Red Centre; the most mythic of Australian landscapes; the Waterloo, as it were, for a number of legendary explorers who got lost and died of thirst; home turf for Australia's classic rustics; and the setting for its creation myths, both Aboriginal and colonial. A place where tourists go and which coastal, urban Australians say they must see some day. As the years go by and the culture loses the immediacy of its connection with the Outback, are Australians becoming just like other coastal, urban peoples? Is the Outback only a place to be exploited for its mineral wealth? Do people in the capital cities care anymore? It’s like the detached attitude Canadians, who are also overwhelmingly urban, have for the “True North” of the Arctic, and Americans in the “southern 48” have for Alaska. And Russians for Siberia? – perhaps not. “So in the end we shall have – if we do not already have – this dual image of ourselves, a schizophrenia of cities and the land. And then I suppose we shall have to go out, like pilgrims in a ritual, in search of our other selves, and the earth and sky, rain and drought, survival and death and fire and ashes, that are all part of us. The lucky among us will always be able to find the ritual in our own experience.” –George Johnston, The Australians, 1965.  Overseas: Just another word perhaps, but one with a profound meaning for many Australians. Often it means a lot more than “we went overseas for a holiday” – the way an Englishman or North American would use the word. You hear many people talk about family members who are “overseas,” for career, education or love, and its use has a sadness about it – the deep dislocation and uprootedness of long separation, the expensive flights to visit, their expat lives. The size of Australia is as daunting as its distance from the rest of the world. The flights to Asia or Europe spend at least 5 hours over Australian territory before escaping its airspace. Los Angeles is 14 hours away on the non-stop. Even New Zealand, that pleasant land of kiwis, sheep and drizzle, is three. P P-Plater: a young, inexperienced driver with a provisional plate (red for the first year, green for the second) on his car to indicate he’s got his license but … watch out! You should probably get out of the way. In the news, a “P-plater” is almost always male, in a car as overpowered as he is over-testosteroned. News reports will say, for example, "Police clocked a P-plater at over 190 km an hour in a school zone ..." Pavlova: the dessert that is WA's major gift to Australian culture (more so even than entertainer Rolf Harris): meringue filled with whipped cream and topped with fruit, especially passionfruit. According to the Macquarie Dictionary, it was created at the Esplanade Hotel in Perth in 1935 and named for the Russian ballerina, who was too thin ever to have been in the same room as one. According to many psychology textbooks, the term "Pavlovian response" means to drool at the sight of a pavlova. (Kiwis claim that Australia stole this delicacy along with Russell Crowe et al.)  Perspiration:less

of an issue now than it was a lifetime ago, perhaps? From Elizabeth:

perspiration was also called BO. [See the vintage Lifebuoy illustration

in the Houses section.] Perspiration:less

of an issue now than it was a lifetime ago, perhaps? From Elizabeth:

perspiration was also called BO. [See the vintage Lifebuoy illustration

in the Houses section.]Pies: almost always meat-filled, or at least savoury, often individually sized and bought as take-aways for lunch. The sweet, fruit-filled dessert that's "as American as cherry pie" would likely be called a tart in Australia and is less popular than a cake or slice. "It was a national tragedy the day that Sergeants stopped baking pies. People went around buying up the last run, and freezing them. It was very sad I remember; we mourned their passing for years, quite literally. The new ones are ok, but not a patch on the original. (Aussies used to have them flown overseas when touring.) It's the highest praise for a pie to say it's almost as good as a Sergeants" – a digression by an anonymous correspondent to the official Vegemite website. Poet's Day: the old colloquialism for Friday, from Piss Off Early Tomorrow's Saturday. Pokies: the poker machines that make Australia's gambling problem a runner-up to its drinking one. They are licensed into the leagues clubs and RSLs in every town and suburb, where you can gamble, drink and dine. Poms: originally English immigrants, but now used to describe the English themselves; if you're one, don't broadcast it, especially in a pub after everyone's had a dozen beers. The current most likely derivation, subscribed to by the pommy publication called the Oxford English Dictionary, goes like this: In the rhyming slang of a century ago, a pomegranate, sometimes written as pummy grant, was an immigrant; as with most other terms it was compressed, becoming "pom," which was then applied to all Englishmen as they were 90+ percent of Australia's immigrants. Ergo, "ten-pound poms," a disparaging term for the impoverished Englishmen who came to Australia after the Second World War on a £10 assisted passage. In those post-war years, wrote traveller Bernd Lohse, "These family differences [between Australians and English immigrants] are either ironed out in one or at the most two years, as with the majority of Englishmen who emigrate or, in a minority of cases, give shipping lines a regular profit as a result of return tickets to Southampton. It is estimated that about 20 percent of the emigrants return to their country again." The amount of ongoing resentment of "The Poms," also known as the Pommy Bastards, relates to the culture cringe – the belief that the English see Australia as an inferior place with a marginal, shallow culture. But what have the English done lately to justify any sense of superiority? How can the current mob take credit for Shakespeare, Dickens, Hardy et al? And if they take credit for the Beatles and Clapton they also have to own Sid Vicious. But Aussies do tend to get pretty hot about it. The sentiment comes out most strongly in the biennial cricket series called the Ashes, where “it's about revenge," and in jokes (which may not be unique to Australia) such as this one. Question: “Where do you put something if you want to hide it from a Pom?” Answer: “Under the soap.” The other historical grievance is the economic one: the Imperial preferential tariff that made Australia the “hewers of wood and drawers of water” (as Canadians used to describe themselves) for the Mother Country. The close economic links, wrote Bernd Lohse in the 1950s, "resulted in the daughter country concentrating on the delivery of those agricultural and mineral products of importance to Britain – wool for the Bradford mills, wheat for bread and cakes, butter, chops and steaks for the larder, gold for the Bank of England, and metals for Britain's large industries. In exchange, Australia received from British factories everything that a land with a high standard of living needs in the way of industrial products." Australia’s successes after the Second World War in becoming a country that “makes things,” especially cars, are now being gradually reversed as manufacturing moves offshore and Australia becomes “China’s mine.” In this, Australia is in good company, as witnessed by the collapse of industrial employment in the USA in the past 20 years. Although there’s a lot more American slang and habits in the country than there were 25 years ago, if you’re from North America you realize right away how English Australia still is. Words like “prat”, “whinge” and “wanker” sound like South London. It’s also veddy English that Australia’s most venerable comic character, Barry Humphries’s Dame Edna Everage, not only has an English title but is a drag queen (in Ameri-speak). Prawns: the term used for all kinds of shrimp, including prawns. |

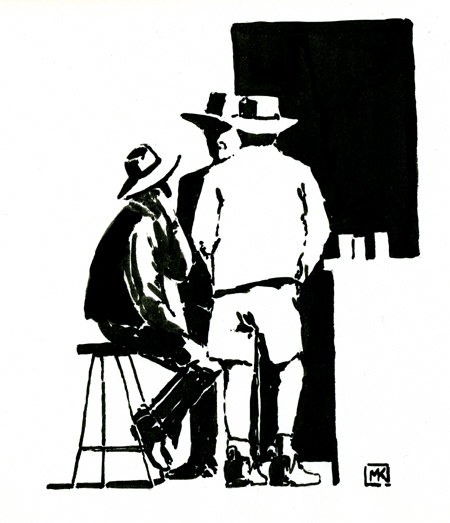

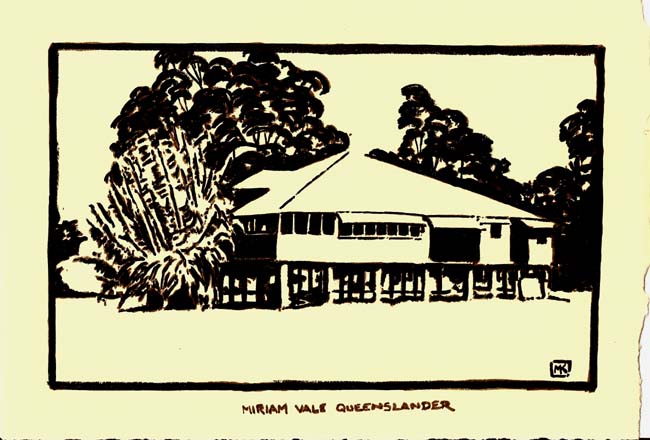

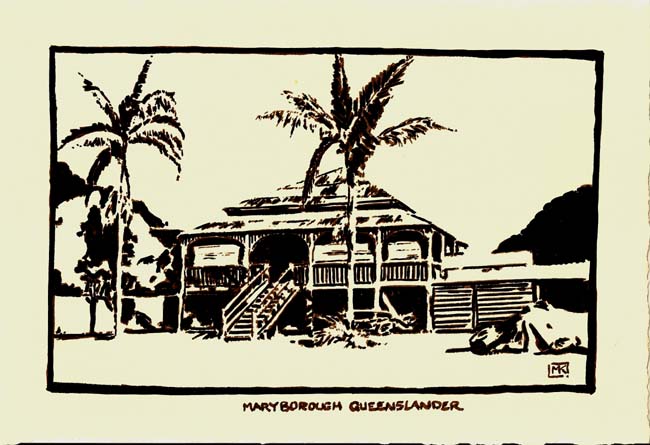

Unlike in Britain, pubs rarely became the “living room” for the people of a village or neighbourhood; instead, they were the bastion of the blokes and probably the greatest hindrance to family life that could have been imagined. In a way they were like a lot of American taverns, a place where a group of like-minded people could while away a good part of their lives unproductively. As in some other countries – most of Canada, for example – the publican’s license was tied to his ownership of a hotel. Guess which part was the most profitable? Not surprisingly, Australian country hotels, together with the low-end city ones, provided rather Spartan accommodation and second-class food. Women did not enter many public bars before the 1970s, or perhaps later, instead being served (if they weren’t at home babysitting the kids or waiting outside in the ute) in the small lounge or saloon bar next door. Men stood to drink. Between 1916 and 1954, Sydney pubs closed at 6 pm; at a guess, 90% of the beer (an estimated 12 gallons per person annually at that time) was consumed in the final hour before closing. The term “six o’clock swill” went into the language, supporting a binge-drinking culture that continues to this day. What other country could have had a prime minister – Bob Hawke – who had held a world record for the fastest chug-a-lugging of a yard of ale? (He balanced his distinctly Australian achievement by being a Rhodes Scholar.) Although the swill is long-gone, the shout continues to ensure that few social drinkers will get out without downing their fill. From Elizabeth: old style pubs also had tiled floors and half walls so the "barf and piss" from the men could be hosed down after closing – the ladies' side was more genteel! Depending on what State you're in and, also, what state you’re in, you will order beer in a pub by the pint, schooner, middy, pony, handle, pot, eight, seven, six, five, glass, bobby or Shetland, according to a list in David Morgan’s “The Australian Miscellany.” J.M. Freeland described the Aussie pub as being the perfect architectural representation of a “brash, young, non-conforming country.” Writing in the 1960s, he saw how the diversity was returning to what had been a strait-jacketed drinking factory in the cities. “But in the lonely country pubs things are much as they have always been. Despite the tremendous changes that the city and town pubs have undergone, in the remote places there are many of the iron-roofed, iron-walled, deep-verandahed havens still filling the place in their own society that their predecessors did. Except for a new kerosene refrigerator, and the old cork-weighted string or bead curtain hanging across the bar doorway, which was intended to brush flies form the shoulders and back of those passing through, being replaced by gaudily-coloured plastic streamers, time has passed them by for several generations.” (p. 198) So the evolution of city and country pubs mirrored the split seen elsewhere in Australian society. Nowadays pubs are easy-going places, whether city or country, with the old blokiness being a distant memory. Q Quarter-acre block: the key element of the suburban dreamscape; the historic birthright of every Australian, leading to suburbs stretching over the horizon around major cities. “The [1860s] saw the creation of suburbs and the pattern of row upon row of individual houses each on its own quarter-acre allotment. The endless sprawl of the former has become the universal characteristic of all Australian cities and towns and the ownership of the latter the universal goal of every Australian. The change was due to the introduction of the railway.” – John Maxwell Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 1968. “The truth is that most Australians are not really urban at all, but suburban, and the city dweller, bustling and bustled as he might be, very often works not for the ambition of ‘getting to the top,’ but simply to achieve private dominion of his suburban plot and the freedom of his weekends and holidays.” – George Johnston, The Australians, 1965. Queenslander: a) in the Australian creation myth, a character rather like a Texan, except lacking the oilfield and wearing a different type of hat. More recently, it's the smart one with a real-estate license who moved to the Gold Coast and struck gold. b) a particular type of timber house, built on stilts to try to fend off the white ants, with wrap-around latticed verandahs and a tall pyramidal roof, well-adapted to the heat and humidity of the Australian North's tropical climate.   R Rabbit: the ultimate introduced pest, far worse than foxes or cane toads, and an environmental disaster non-pareil. Five rabbits entered the continent on the First Fleet in 1788; like their fellow convicts, they remained captive, but subsequent arrivals escaped and established feral populations in Tasmania before 1830. On the mainland, in 1859, a clutch of bunnies was released from a farm in Victoria to provide the farmer with some sport, inadvertently unleashing a plague onto the land and its native inhabitants. “The rate of spread of the rabbit in Australia was the fastest of any colonising mammal anywhere in the world and was aided by the presence of burrows of native species and modifications to the natural environment made for farming. Rabbits are now one of the most widely distributed and abundant mammals in Australia.” – feral.org.au. Myxamotosis, introduced in 1950, reduced the populations to a small fraction of what they once were, estimated in the billions in the 19th century. Their ability to breed like rabbits created a job for the rabbitohs, who shot them and carried braces of them around door to door, through towns and suburbs, selling them at sixpence-a-pair to housewives. The resulting rabbit stew was a real poverty food – a “common dinner” – befitting the hardscrabble lives so many then lived. The inference that Australia had many rabbits, and that they were a problem, went into the international consciousness recently again due to the title of the movie “Rabbit-Proof Fence,” which had nothing at all to do with rabbits. Nowadays, rabbits are too cute to eat! Indicative of the decline of traditional Australian culture, and the separation of the mass of its population from rural concerns, it is now hard to find rabbit on menus and in butcher shops. Few people now have a taste for it and even fewer endure the poverty that in the past drove so many families to eat it regularly. And it never caught on as a gourmet dish. Just like elsewhere in the western world, the modern Australian rabbit is the Easter Bunny, bringing colourfully wrapped packages of tooth decay and Type-2 diabetes to children everywhere.  Tracks

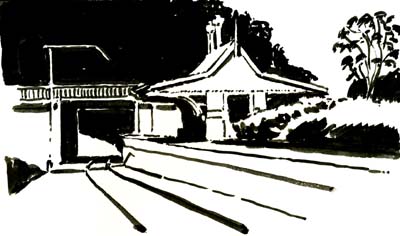

and an old railway gatekeeper's cottage on the outskirts of Goulburn,

NSW

Railways:used to be an object of pride in spite of being only semi-functional due to the mix of rail gauges from State to State. In the railways’ heyday even the grandest trains, such as the streamlined Spirit of Progress, the pride of 1930s Victoria, travelled from Melbourne only as far as the little town of Albury on the NSW-Victoria border, where passengers had to disembark and board a Sydney-bound train that ran on the NSW gauge. (The railway-gauge story is an example of a broader theme in Australian society – turf wars between the States, leading to problems of national significance such as the over-allocation of water along the Murray-Darling river system.) Although the breaks of gauge between States have since been sorted out, passenger-train service in the country is just a shadow of its former self. Yet much of the nation’s railway infrastructure survives and it is an astonishing legacy for a non-European country. Such a mix of images come to mind: the grand stations of the big cities and the beautifully crafted country stations; the suburban stations with their adjoining shopping centres on the Sydney train lines; the railway hotels in country towns. Unfortunately there aren’t that many trains anymore except to move people around in the capital cities. The country’s vast distances are better tamed by aviation, and whatever efficiency the rail networks once had proved unequal to the demands of modern commerce, which prefers the flexibility of trucks running on crowded, potholed, publicly subsidised highways. Only the bulk cargoes, such as coal and iron ore, now move by rail. The grand, romantic train routes, such as the India-Pacific from Sydney to Perth and the Ghan from Adelaide to Darwin, mainly benefit tourists. From Elizabeth: I disagree with you about trains - they were excellent on the trip to the north coast and back - very clean, on time, relaxing in those comfy seats - the 2 "rowdies" were given a talking to by train security guys and put off at the next station so I felt very at ease on the trains chatting to people. Passengers get free "bikkies" with the am & pm tea and coffee. Hot lunches & dinners are available and you can buy wine to go with them - all packaged nicely in a cardboard tray to avoid spills and burns. Food wasn't great for vegetarians but they at least tried to provide that option and my spinach lasagna was very filling!  The

tiny Medlow Bath station in the Blue Mountains, NSW

Rego: the combination of paperwork, inspection and insurance you need to put your car or ute onto the road. Rellies (or rels): the extended family who, if you’re a newcomer, are probably overseas. Rev-heads: like hoons – in the sense of fast-driving – except usually with no connotation of illegality. They are lovers of V8s, loud exhausts, races and other activities where petrol is turned into fun. Roo-bar: a) a place where a kangaroo might hop in for a drink. ("We don't get many roos in here," the bartender remarks. "And at these prices you won't get many more," answers the roo.) b) the welded bars on the front of a 4WD or ute like the cow-catcher on the front of a locomotive. Called a bull-bar sometimes. Rort: the verb for swindle. People rort their expense accounts or the tax department, for example. An all-too-common activity of leading businessmen and politicians, alas. Also a noun. RSL: the Returned and Services League, known as the Returned Services League from 1965-90. It would be called the Legion overseas, and is anglophile and monarchist – ergo, its support for the current flag. The RSL Clubs are the centre of social life in many suburbs and country towns, indistinguishable from the Leagues and Bowls Clubs with their dining rooms, bars and pokies. Its big events are ANZAC Day (the 25th of April) and, much smaller, Remembrance or Armistice Day on the 11th of November. S Sausage Sizzle: a kind of public barbie featuring – you guessed it! – sausage on a bun, the main item on a short menu that might include egg-and-bacon sandwiches. Outdoor community meetings and fairs often feature them and they’re always easy to find – you just follow your nose. The use of the term "snag" for a sausage has declined, it seems, normally appearing only in butcher-shop windows in country towns. Seppo: Derogatory word used by the English and Australians for all American nationals. Derived from rhyming slang (Septic Tank = Yank). Submitted by Sandra, "confirmed" by urbandictionary.com. Service: something that customers occasionally receive. A foreigner might reckon that the lack of it in restaurants correlates with the lack of tipping, and the lack of servers might have something to do with the high minimum wages. But for all the insouciant, gum-chewing, bored louts in shops and cafes who sarcastically say “pleh-jah” when you thank them, there are as many eager, friendly and helpful ones. There is a long tradition of comments about service in Australia. Some writers equated the lack of it with the country’s egalitarian ideals. In 1922 D.H. Lawrence felt that “the best society in the country are the shopkeepers – nobody is better than anybody else, and it really is democratic.” In the 1950s, German visitor Bernd Lohse let loose a memorable rant on the matter: “Every writer travelling in Australia must devote at least one chapter to the tiresome absurdities of daily life. They are there and they often make the legendary high standard of living look a little like the curate's egg to European or North American eyes. Here is a 'standard of living' sum: a little house with a garden in a usually sunny climate; leisure time for picnics and sport, and enough pocket money for them too; food and fruit full of calories at reasonable prices, even to the custom of steaks for breakfast which so shocked me at first; exemplary welfare for children and old age pensioners; and a decent wage even for the most modest job. Yet with all that I, like every foreigner, was amazed at the lamb-like patience with which the Australians accept the almost total lack of service in the widest sense of the word. “On my first day in an Australian hotel I missed the clothes-hanger though later I got used to this. Since it was the time of morning at which the room was cleaned I managed to find a maid in one of the rooms. "Clothes-hanger? Haven't got them any more. You could have had one a few years ago. But then one or two guests borrowed them and since then the manager won't hear of hangers. You want to tell him? Know what he'll say? 'I couldn't care less!' Do you know what? I'll get you one. When we have posh guests, you see, who can't get along without a clothes-hanger, then they make themselves one. It's easy – look!" When she came back she was dangling an ingenious construction from a piece of string. It was the massive Sunday edition of a Sydney paper rolled up tightly and suspended by a string, and made the simplest sort of coat-hanger. “Another factor which militates against good service is the maddening pride of the lowliest employee who feels that too much 'help' and 'politeness' are signs of an undignified servility – this help which, even in the USA, or rather particularly there, is counted simply as 'part of the service' given by an employee.” Servo: the place where you fill up with petrol. Shed: a structure where a bloke keeps his stuff. Said to be one of the best marriage-savers ever invented. The term "barn" is not used in Australia, mainly because there's little need to bring animals inside to protect them from harsh weather. When there’s an ancillary building on a farm it's called a shed, for example on a sheep property where you'd find a shearing shed.  Illustration

by an unknown artist from the Pictorial Social Studies

school textbook series, c. 1960.

Sheep: the dots like cotton balls on the Australian landscape; alchemists that convert grass and twiggy shrubs into the only fibre that will keep you warm in the sharp winter winds; four-legged anachronisms in a world that wants to wear cotton and polyester and worries about eating too much meat. There are about five of them for every human in Australia but, in spite of those odds, there's little chance they'll gain control. Second only to New Zealand, Australia was built “on the back of the sheep,” yet their role in the country’s economy is waning as fast as the sheep themselves fade from the collective urban memory. A couple of generations ago, before there was any concept of renewable resources and sustainable industries, schoolchildren learned from books like the one above. Today, when they’re taught about resources and the economy, the subject will likely be the shipment of non-renewable resources – iron ore and coal – to China and Japan. The overseas perception of Australia included flying doctors, boomerangs, roos, koalas and sheep. Yes, sheep. They are a major part of the Australian legend. So it is a surprise to find how invisible they now are, in the sense that they’re out of sight (in the country where nobody goes), out of mind. They are truly an industrial animal: there are myriad cute toy animals in the shops for children, but it’s almost impossible to find a cute toy sheep. A few tea towels feature printed images of sheep, but in artwork they only appear occasionally in the most traditional of landscapes. Their existence, and the farm families that depend on them, seem a million miles away from the concerns of most Australians. Once they were like gold – now the country’s gold is the Gold Coast with its sun and surf, or the black gold of coal loaded onto a ship.  Australia’s

main crop in the post-war era, from

“The Story of Australian Wool.”

Yet in spite of its relative insignificance to the economy, the quality of Australian wool is unsurpassed. When a prize-winning bale of superfine merino sells for an astronomical sum to a luxury suit-maker in Italy, there will be a brief news story in the papers to break the silence. It is an irony that the merino, ranging across the sere plains of the wide brown land under a pitiless sun, produces the finest and softest wool in the world. Merinos were Spanish sheep known in Roman times. A flock made it to England around the time of the establishment of the Australian colony and did alright, but the settler John Macarthur, of the Elizabeth Farm near Parramatta, thought Australia’s climate ideal for them and managed to obtain some from South Africa. The key to their success has been the low level of nutrition in the native Australian grasses and, thus, the constant state of slight undernourishment in which they spend their lives. The result is a uniformly thin wool fibre, perfect for high-quality, fine-yet-warm garments. With so many sheep around, it’s no wonder lamb is cheap. Somebody has to do something with all the excess boys and anybody else whose fleece doesn’t make the grade, so traditional Australians invite them to barbies, as it were. Sheila: a female bloke, not a term you hear much anymore.  Shops: traditionally, the commercial area of the main street of a town or adjoining the railway station in a suburb. Sometimes called the shopping village or shopping centre but, increasingly in recent decades, the latter term has come to refer to the North American style of enclosed, air-conditioned mall surrounded by parking. Many of them are owned by Westfield, an Australian company owning many many malls in the USA. The old streets of shops are very distinctively Australian – a jumble of parapets, solid awnings that sometimes abut each other along a street, and buildings in different styles and finishes, a few highly decorated with Victorian gewgaws, others very simple. A butcher; a greengrocer; a baker of white bread, cakes and slices; a newsagency; a café or two, probably; a bottle-oh, in some cases attached to a hotel with a pub; likely a real-estate agent and a hardware store; once upon a time, a milk bar. As these streets are gradually modified or eliminated, due to changing shopping habits, road widenings and more drive-in whatevers, Australia loses another part of its uniqueness. Shout: not what you do to get the bartender's attention, but your turn to buy the drinks. "Yer shout mate" means "git up there and buy a round for everyone." In John O’Grady’s comic immigrant novel of the 1950s, "They're a Weird Mob," made into a film in 1966, Italian newcomer Nino Culotta has a hell of time understanding what is expected of him when he goes to the pub and a stranger buys him a beer. When he’s told it’s “Your turn to shout” he becomes confused and, not wanting any more himself, he offers to buy the stranger a drink. This, he finds, is a major faux pas, as the stranger considers it insulting that Culotta won’t drink with him. Another way to use the expression is, for example, "it's my turn to shout lunch." The ritual of shouting your mates leads inevitably to everyone having half a dozen drinks before they can stagger home. In the mixed tables at modern Sydney pubs and nightclubs, the habit of shouting is a great benefit to the men, who get a lot more drinks bought for them than their women companions can possibly consume.  Show Bag: at a fair, a bag of samples, probably including a toy or gadget or gimmick, from one's favorite candy company or other exhibitor. At the Royal Easter Show in Sydney, they cost $30-35. Slab: a 24-pack of beer cans The Snowy: the Australian alpine, straddling the NSW/Victorian border. It’s part of the legend of the country in its colonial days due to Banjo Patterson's ballad “The Man from Snowy River.” More recently, the Snowy hydroelectric scheme of the post-WW II period saw Australia for the first time manipulate its natural environment in a major way. And, it’s the place to go to see the white stuff where, in a cold winter, you might get in a bit of skiing. It’s closer than New Zealand for most Australians, but only just (time-wise, at least). Spruik: to promote, a word like stoush that appears regularly in newspapers. Stoush: a fight.  Sun: one of Australia's great tourist attractions, and what ought to be a huge electrical energy source but isn’t yet because coal is just too easy to dig up and burn, making Australia the nation with, per capita, the largest greenhouse-gas footprint. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Industrialised Countries: Where Does Australia Stand? The Australia Institute Discussion Paper 66, June 2004. And, of course, Australia is the sunscreen capital of the world, with more skin cancers per capita than, say, Ireland. Super: short for superannuation, the government-encouraged savings scheme for workers where income is sheltered for the retirement years, to supplement the public old age pension and hopefully keep the elderly from consuming too much dog food.  Surf: Australia's greatest tourist attraction, or so it seems sometimes. Actually, according to the Future Brand survey that ranked Australia the #1 Brand in the world (see Tourists), Australia’s beach experience is fifth in the world after this set of one-trick ponies: Maldives, Tahiti, Bahamas and Dominican Republic. Swag: a bundle of possessions, often referring to stolen goods. An itinerant worker or drifter carrying his swag is a swagman or swaggie, like the "jolly swagman camped by a billabong" in the national song. His bedroll was his "matilda" and "Waltzing Matilda" (the name of the national song) meant going out on the road; when you rested on your bedroll by the campfire, you were "lying in the arms of Matilda." |

|

|

|

|

|

Contact me Return to home page